This theoretical study establishes a theoretical framework for resonance-oriented music mediation, aimed at fostering strong music experiences. It introduces a model designed to conceptualize and analyze music mediation projects that seek to initiate, broaden and deepen music relationships. First, the understanding of music is discussed and it is explained how the fields of cultural studies, the capability approach and music sociology contribute to the theoretical foundation of music mediation. Music mediation is then discussed as an umbrella term encompassing diverse practices. The second section builds on Hartmut Rosa's (2016) resonance theory, which describes resonance as a dynamic, reciprocal interaction, to establish the core principles of resonance-oriented music mediation. The proposed model, informed by additional literature, delineates (1) four dimensions of resonant music relationships, (2) their defining characteristics, (3) favorable impulses, and (4) underlying principles. These theoretical findings are illustrated with a practical example. The article concludes with a discussion of the ethical implications of resonance-oriented music mediation, emphasizing the facilitation of vibrant and transformative music relationships.

Cet article établit un cadre théorique pour la médiation de la musique, avec pour toile de fond le concept de « résonance », visant à favoriser des expériences musicales marquantes. L'auteure présente un modèle théorique conçu pour conceptualiser et analyser les projets de médiation de la musique qui cherchent à initier, élargir et approfondir les relations musicales. Elle aborde tout d'abord la compréhension de la musique et explique comment les domaines des cultural studies, de l'approche par les capability et de la sociologie de la musique contribuent à la fondation théorique de cette approche de la médiation de la musique. L’article souligne ensuite les multiples modalités d’action pouvant être regroupées sous l'appellation « médiation de la musique ». La deuxième section s'appuie sur la théorie de la résonance de Hartmut Rosa (2016), qui décrit la résonance comme une interaction dynamique et réciproque, afin d'établir les principes fondamentaux de la médiation de la musique axée sur la résonance. Le modèle proposé définit les quatre dimensions des relations musicales résonantes, leurs caractéristiques, les impulsions favorables et les principes sous-jacents à une telle relation. Ces résultats théoriques sont illustrés par un exemple pratique. L'article se termine par une discussion sur les implications éthiques de la médiation de la musique axée sur la résonance, en mettant l'accent sur la facilitation de relations musicales dynamiques et transformatrices.

Dieser Artikel legt im Rahmen einer hermeneutischen Literaturstudie eine theoretische Grundlage für eine Resonanzaffine Musikvermittlung, die starke Musikerfahrungen begünstigen will. Die Erkenntnisse werden anhand eines Modells dargestellt, das zur Konzeption und Analyse von Musikvermittlungsprojekten dient und darauf abzielt, Musikbeziehungen zu initiieren, zu erweitern und zu vertiefen. Zunächst wird das Verständnis von Musik erörtert und erläutert, wie Ansätze aus den Kulturwissenschaften, dem Capability-Approach und der Musiksoziologie zur theoretischen Grundlage der Musikvermittlung beitragen. Musikvermittlung wird anschließend als ein Sammelbegriff für verschiedene Praktiken betrachtet. Im zweiten Teil werden die Beschaffenheit von Musikbeziehungen unter Einbezug der Resonanztheorie von Hartmut Rosa (2016) untersucht und das Modell der Resonanzaffinen Musikvermittlung in Form einer Drehscheibe erläutert. Die vier einzelnen Scheiben des Modells umfassen die (1) vier Dimensionen von resonanten Musikbeziehungen, (2) deren definierenden Merkmale, (3) begünstigende Impulse sowie (4) grundierende Prinzipien. Die theoretischen Erkenntnisse werden mit einem Praxisbeispiel veranschaulicht. Der Artikel schließt mit einer Diskussion der ethischen Implikationen der Resonanzaffinen Musikvermittlung und betont die Förderung lebendiger und transformativer Musikbeziehungen.

music mediation, resonance, interaction, artistic citizenship, assemblage

This article seeks to establish a theoretical foundation for music mediation from a sociological perspective. Building on this foundation, it proposes a model adaptable to diverse music mediation contexts. It is premised on the assumption that music mediation aims to create, broaden, and deepen music relationships (Müller-Brozović 2017; Petri-Preis and Voit 2023), thereby fostering strong experiences with music (Gabrielsson 2011). The model views music mediation as interaction and is therefore based on a relational approach. Instead of focusing solely on the subject or the musical work, it emphasizes the interconnections between participants. Through this interaction, all participants undergo change, with these transformations unfolding as an open and dynamic process.

Resonance-oriented music mediation is guided by societal challenges and rooted in the shared resources and perspectives of all participants. It is committed to sustainability and the common good, aiming to create co-creative spaces that promote cultural participation through diversity and development. The approach outlined here values tradition, while critically examining its contemporary relevance and application. It is grounded in everyday life, oriented toward the future, and open to transformation. Consequently, resonance-oriented music mediation is understood as a practice of “musicians as makers in society” (Gaunt et al., 2021). These artistic citizens1, or “artizens” (Bradley, 2018; Carson and Westvall, 2024; Elliott et al., 2016; Garcia-Questa, 2024), blend artistry with social responsibility and ethical practice.

This article explores the quality of music relationships within music mediation across various settings – on stage, in communities, in media, and in other areas. Rather than offering a strict definition of music mediation, it presents a glimpse into a complex theoretical foundation that can only be briefly outlined here (for a full discussion, see Müller-Brozović 2024).

The central question of this article2 is: What theoretical model can represent the creation, broadening, and deepening of music relationships, as well as the fostering of strong experiences with music? To answer this, the article engages in a literature review, drawing on research in music education (Krupp-Schleußner 2016; Schmid 2014;), musicology (Cook 2013; Leech-Wilkinson 2020; Small 1998), performance studies (Fischer-Lichte 2004; 2012), cultural studies (Hornberger 2020), and sociology (Rosa 2016). Key findings are illustrated through practical examples. Methodologically, this study is a theoretical, hermeneutic exploration, not an empirical investigation. It builds on a completed dissertation (Müller-Brozović 2024) which developed a model accompanied by guiding questions for use in diverse areas of music mediation. Ideally, context-specific and personally relevant questions are developed and explored for each aspect of the model. This approach does not aim to define specific practices but to reveal the entanglement of various practices, each of which takes shape in distinct ways. I hope that the model presented here will support a nuanced description of the qualities of individual music mediation practices.

The article begins by clarifying terms and individual understandings. First, I discuss the understanding of music that underpins resonance-oriented music mediation. I then examine how cultural studies, the capability approach and a mediation theory from music sociology inform this approach. Next, I unfold music mediation as an umbrella term and show its various meanings. In the second part of the article, I present a theoretical foundation for music mediation, drawing on Hartmut Rosa’s (2016) resonance theory and framing resonance as vibrant, dynamic interaction. I then introduce a model of resonance-oriented music mediation, incorporating additional literature. This model outlines the defining characteristics, the four dimensions of resonant music relationships, favorable impulses, and the underlying principles of resonance-oriented music mediation. Finally, the article demonstrates how the model can be employed to design and analyze music mediation projects with ethical considerations linked to a resonance-based approach.

The resonance-oriented music mediation discussed in this article is based on Christopher Small’s (1998) concept of musicking, which applies to all forms of music genres and musical activities. The term ‘musicking’ indicates that music is an activity. Everyone involved in this practice, in various ways, engages in musicking. This includes those who perform music, listen to it, organize concerts or workshops, write or post about music, dance to music, produce videos, or participate in any other related manner. The concept of musicking implies that music mediation is embedded within a network of music relationships, from which meanings emerge.

Following Small (1998, 218), musicking is a practice of exploring, affirming and celebrating relationships, and of fostering social solidarity. This complex web of music relationships relies on physicality and gestures, aspects that words alone cannot fully grasp. According to Small (1998, 140) “In all those activities we call the arts, we think with our bodies”. Consequently, the physicality and corporeality of musical relationships – reflected in the German terms Körper (having a body) and Leib (being a body) – are essential to the music mediation approach discussed here.

Small (1998, 112) views a score as a set of coded instructions for musicians, while Nicholas Cook (2013, 306) regards notation as material for the artistic process, suggesting that performers not only play a piece, but rather play with the piece. By embracing this interpretative freedom, musicians realize their agency within the creative process. Musicologist Daniel Leech-Wilkinson (2016, 333) thus advocates for performers to embrace radical performance, engaging freely with the music and score. Resonance-oriented music mediation promotes such creative engagement with music as both a social and aesthetic practice. However, it also includes musical practices that adhere closely to notation or, in contrast, embrace improvisation and oral traditions. The understanding of music described here breaks with traditional assumptions of Western art music and, following Small, recognizes physical, performative, media-related and interdisciplinary aspects of music as part of musicking.

Resonance-oriented music mediation aligns with the cultural studies perspective (Hornberger 2020, 51) that music mediation is interwoven with power relations. The common assumption that Western art music inherently promotes personal development creates a knowledge and power gap3: people who prefer so-called popular music and find little interest and meaning in Western art music are often not only considered to have bad taste, they are assumed to have cognitive, moral and social deficits, too (Hornberger 2020, 52). The frequent emphasis on mediation at eye level reveals a mismatch here. Cultural studies scholar Barbara Hornberger (2020, 52-54; 58-59) therefore warns against mediating music taste and pleads for giving up interpretive supremacy. She argues that enjoyment and pleasure should also be recognized as part of educational processes, and she advocates a music mediation free from extra-musical goals, such as audience development or social integration of certain dialogue groups. Such a music mediation does not require transfer effects. By resisting these neoliberal cultural policy agendas, music mediation becomes subversive – for the joy of music and for enabling strong musical experiences from which meaning, empowerment but also resistance can emerge (Hornberger 2020, 59-60). This is the core of resonance-oriented music mediation: it emphasizes personal relevance and the many qualities of different music relationships. Instead of aiming for extra-musical effects, it seeks to foster a space of opportunity for musical affection (in the sense of being addressed) and involvement.

Since music mediation is a practice of musical involvement, it is inherently cultural participation – a recognized human right4. Therefore, the capability approach, a theory of justice, will be briefly discussed here. The aim is to explore who is given the opportunity to become musically involved and whether this is desirable at all. Music educator Valerie Krupp-Schleußner (2016) has applied the capability approach, developed by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum, to these questions. Unlike absolute measures of justice, the capability approach emphasizes comparative justice, aiming to support a good life in which each person can choose a way of life they consider meaningful and valuable (Krupp-Schleußner 2016a, 4). Capability encompasses a person’s rights and resources. It is only with structural and individual functioning (including, among other aspects, participation in music mediation, as well as a personal openness) that a person acquires agency with different options.

Crucially, participants retain the freedom to choose among these various options, including opting out of musical participation. Non-participation, if a conscious choice, is seen as an expression of agency rather than a negative outcome (Krupp-Schleußner 2016b, 80). Resonance-oriented music mediation, therefore, seeks to create inviting opportunities for participation, while respecting non-participation as a valid choice, free from judgment. As mentioned above, this approach does not aim to shape musical taste or foster audience development, but instead acknowledges that music mediation may also lead to alienation.

The term Musikvermittlung [music mediation] has been used in German-speaking countries since the 2000s for special concert formats, participatory workshops, collaborations between music ensembles and social or educational institutions, and media-based mediation formats such as program booklets or podcasts (Petri-Preis and Voit 2024 in this journal). It has not yet become established in English-speaking countries. However, there is a mediation theory5 formulated by renowned music sociologist Georgina Born (2015) which, although she analyzes the general nature of music, also seems well-suited for a theoretical foundation of doing music mediation in a more specific sense. In her mediation theory, Born describes music as a constellation of various phenomena in mutual relationships. Thus, music exists in diverse forms and arises in mediations “between musician and instrument, composer and score, listener and sound system, music programmer and digital code”, forming “a musical assemblage, where this is understood as a characteristic constellation of such heterogeneous mediations” (Born 2015, 359-360). Understanding music mediation as an assemblage clarifies that it involves heterogeneous rather than homogeneous practices, each forming “a particular combination of mediations (sonic, discursive, visual, artefactual, technological, social, temporal) characteristic of a certain musical culture and historical period” (Born 2005, 8).

In other words, music mediation can be conceptualized as a practice of music-

specific interactions within an assemblage of particular constellations. These constellations generate certain patterns and structures, which in turn influence and transform one another reciprocally. Consequently, music mediation is not solely audience-focused; it also engages and transforms musicians and institutions. I refer to this process of internal transformation among musicians and within institutions as intra-music mediation (Müller-Brozović 2024, 175).

Viewed as an assemblage, music mediation does not follow strict hierarchies; rather, it is hybrid and permeable, reflecting and changing existing power structures. An assemblage integrates diverse strands and layers, allowing for unexpected developments and interactions that resist complete planning and control. This dynamic means that interactions within assemblages are not strictly synchronous, but are based on responsive, resonant relationships, a concept that will be further explored later. In the context of music mediation, an assemblage takes form as a forum (Müller-Brozović 2018), providing a space where musicking unfolds within a rhizomatic network of

socio-aesthetic practices (Müller-Brozović 2024, 296).

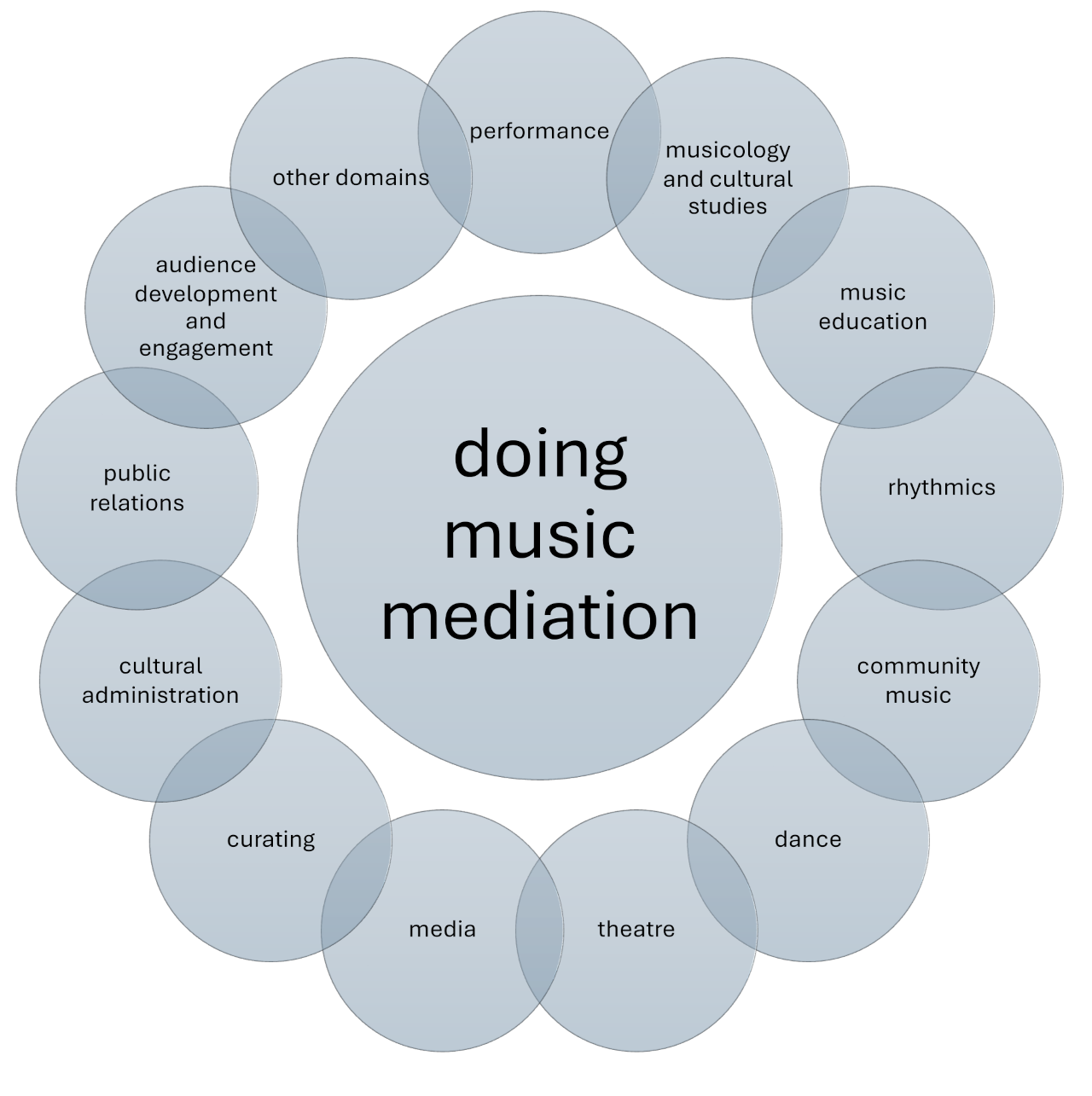

Music mediation can serve as an umbrella term, similar to the way that Musikvermittlung in the German-speaking context acts as a semantic bracket for a variety of music- and society-related activities (Müller-Brozović 2017). What do music mediators do, whether they are employed by an institution or are independent? They perform, give concerts, conceive, organize, and realize concerts, workshops, and projects. They create music, atmospheres and spaces, coordinate cooperation projects, collaborate with other artists and amateurs, and communicate, moderate, write, post, and film within the context of music and society. They contextualize and stage music, curate programs, concert series, and festivals, and/or work in the field of cultural management. Music mediators’ artistic and professional backgrounds, as well as their fields of action, can be quite diverse, including performance, musicology, music education, rhythmics, community music, dance, theatre, journalism and media, curating, cultural studies, cultural administration, public relations, or audience development and engagement, among other domains (cf. Fig. 1).

As part of an assemblage, music mediators work in interdisciplinary, intercultural, and intergenerational teams, collaborating with both experts and amateurs, while frequently engaging in perspective shifts. In German, the term Vermittlung encompasses various meanings. It can involve conveying “an impression, a feeling, a notion, a message, knowledge, information, contacts, or values.” (Müller-Brozović 2017) Mediation may entail social clarification, the transmission of information and knowledge, as well as facilitating and creating experiences and effects as a prerequisite for empowerment. Mediation always implies communication. The German word vermitteln derives from Mittel [mean] or Mitte [middle], which connects, but also separates, two entities. Indeed, in Middle High German, vermitteln also meant to disturb. Paradoxically, nowadays, a synonym of vermitteln is also to reconcile. Regarding music mediation, this ambiguity implies that activities associated with music mediation can serve different functions, from affirming to irritating and transforming (Müller-Brozović 2023a). The focus of doing music mediation lies in experiences, both aesthetic and social, which create a personal and/or societal relevance of music, and can trigger personal, aesthetic, and structural transformation processes. This also includes the aforementioned intra-music mediation, which aims to change not only individual attitudes and practices on a personal level, but also constructs and processes of institutions and organizations on a structural level.

Having explained the general aspects of music mediation, the focus is now on the nature of vibrant music relationships and how strong music experiences can be fostered through such interactions. As outlined above, drawing on Georgina Born’s perspective, music mediation is understood as an assemblage, involving an entanglement of various aspects. Doing music mediation unfolds as interaction in a rhizomatic conception, where there is no center, but rather different manifestations of interconnected phenomena.

In examining musical relationships, this study also draws on sociology, specifically Hartmut Rosa’s (2016) theory of world relations. Rosa’s theory arises from his analysis of modernity (Rosa 2013), which he argues is stabilized through constant acceleration and expansion. This drive for innovation and growth is intertwined with power dynamics (Rosa 2018b, 24) and is evident in music mediation, too (for example through the pressures surrounding audience development).

In this article, I outline only the basic theoretical framework for resonance-oriented music mediation. I have undertaken this in more detail within the context of a theoretical literature research, which was published in German (Müller-Brozović 2024).

According to Rosa, the essence of vibrant world relations lies in resonance. By this, he means lively interactions between independent voices and entities that transform one another through their interrelationship. Resonance, then, refers not to consonance and harmony, but to a dynamic mode of relating characterized by mutual responsiveness – a concept that can be termed responsive resonance. It is not about synchronization, nor about agreement or attention, but involves an active process of mutual listening and responding. This quality of responsive resonance is essential for both making music and mediating it.

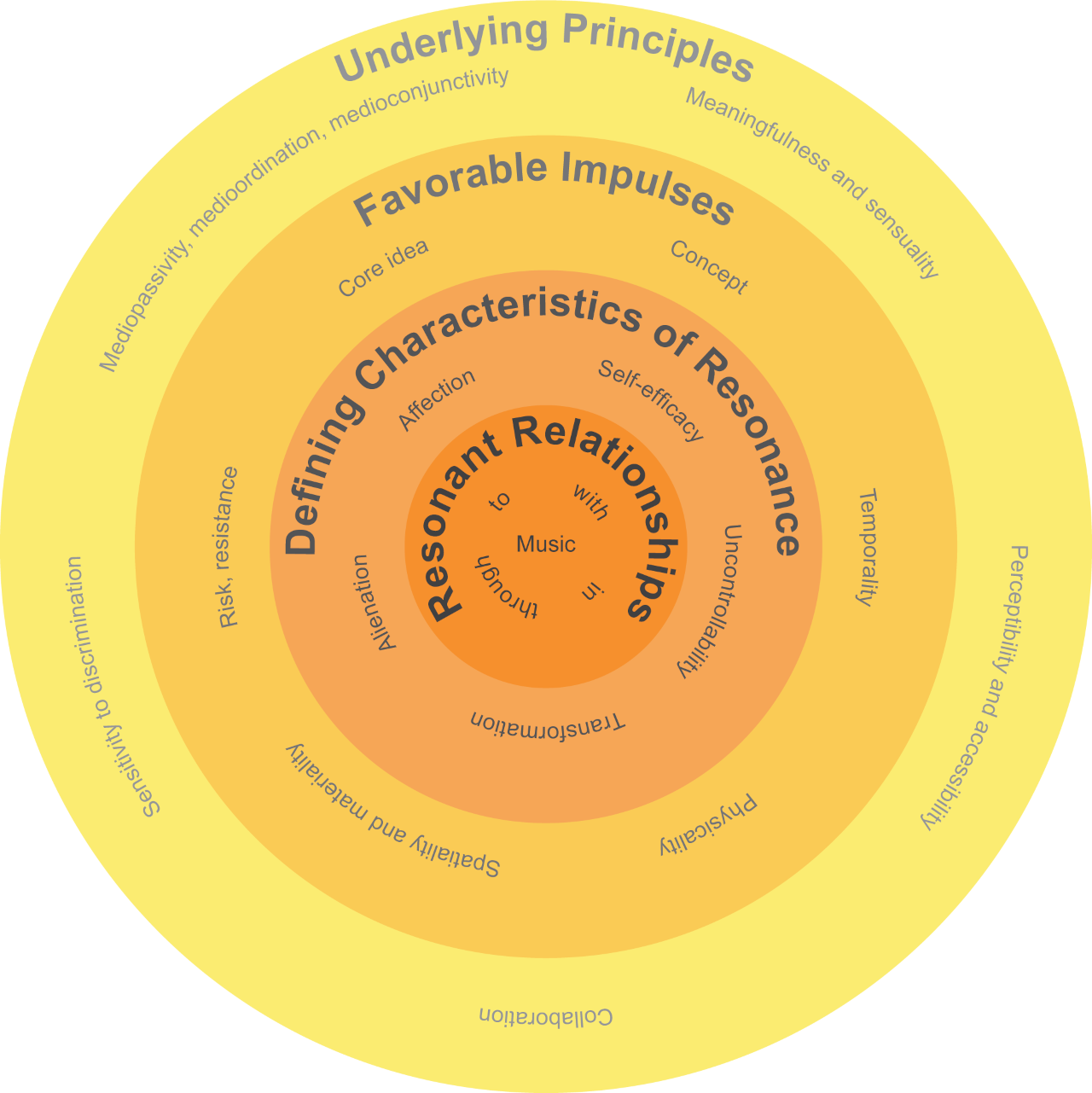

In the following section, I will explain a model of resonance-oriented music mediation (cf. Fig. 2) which I myself have developed and which can be used for the conception and analysis of music mediation projects. For this, I suggest guiding questions that can be taken from my publication (Müller-Brozović 2024, 365-368) or formulated independently. The model consists of four discs and forms a turntable, allowing for various constellations of the respective aspects. The model aims to enable a change of perspective and represents music mediation as an assemblage. The four discs include (1) the four dimensions of resonant relationships, (2) the defining characteristics of resonance, (3) favorable impulses and (4) the underlying principles of resonance-oriented music mediation.

To make the theoretical explanations more concrete, I illustrate each aspect with a specific example. However, in everyday practice, not all aspects need to be considered (apart from the defining characteristics on disc number 2). The example used here is a short video report of a concert by pianist Marino Formenti entitled Time to Gather6. For his concert, Formenti formulates the following concept:

TIME TO GATHER is a piano concert of a special kind:

without a program, without a predictable ending, without the invisible wall that separates artist and audience.People can move around, sit, lay under the piano.

They can interact, and choose with the pianist what to listen to, or play or sing with him and instead of him.They can sit alone or together, lay down, go out for a drink and come back.

Time and togetherness are different, music flows accordingly.

A large number of compositions have been prepared and lie on a table for everybody to look at and to choose from, music dating from the Middle Ages to the present day. (Marino Formenti)7

This concept is by no means an instruction manual for resonance, but only serves to concretize the theoretical explanations. Even though the model is discussed using the example of a new concert format in the field of Western art music (the video shows that a pop song and a Syrian song are also played; the selection includes pieces by Brian Eno, John Lennon and Nirvana), the theoretical foundation and model can also be applied to completely different genres of music and music mediation settings.

Since the defining characteristics of resonance are located on the second disk here, I will start with that. It concerns affection, self-efficacy, uncontrollability, transformation and a possible alienation8. In order to be able to speak of resonance, all of these aspects must be present. However, this corresponds to a subjective situational appraisal, which shows that, although resonance is a phenomenological experience, it can hardly be scientifically proven on an empirical basis.

An affection occurs when something touches and moves me and has meaning for me in its own right (Rosa 2018b, 38-39). This could be a person, an object (such as an instrument), an idea, or a piece of music that gains personal significance and thus relevance for me. In the concert Time to Gather, for example, it could be the idea that, as a listener, I am invited to suggest a piece of music. I am addressed by this and become engaged: I select a piece of music, and it is played for me personally. While listening, the music touches me (perhaps) in an intense way.

Self-efficacy is interrelated with affection. Those involved in a resonant relationship move others and experience themselves as effective. In this interaction, all the individuals involved maintain a certain degree of autonomy (though this is not absolute, since they rely on each other), which precludes manipulation. In the interplay of affection and self-efficacy, we are connected to the world and to people in a lively way, experiencing the world as inspiration and also shaping it ourselves (Rosa, 2018b, 39-40; 2016, 148-149). As an audience member of Time to Gather, I can suggest a piece of music to the pianist. While my piece is being played, I (and the pianist) shape a small piece of the world.

Uncontrollability, as a defining characteristic of resonance, also ensures that no manipulation takes place. Resonant relationships cannot be fully planned and controlled; the occurrence of resonance can neither be forced nor prevented (Rosa 2018b, 44-45). Uncontrollability is also the reason why there can be no instruction manual or checklist for resonance, and the approach presented here is called resonance-oriented (in German: Resonanzaffin). Due to their uncontrollability, situations can be created that favor possible resonance, but do not guarantee it. Whether the chosen piece of music actually speaks to me and affects me during the concert remains open; neither the pianist nor I as a listener can control this. Ultimately, every musical situation is unpredictable and uncontrollable: even if rehearsed down to the smallest detail, unforeseen events occur when making music and help to bring the musical moment to life.

The interactive and uncontrollable nature of resonance makes it clear that resonant relationships bring about a transformation that is open-ended. A transformation, as a defining characteristic of resonance, can manifest, for example, in a temporary change of mood or in a key experience, where, for instance, a fundamental attitude is altered (Rosa 2020, 399-400). It may be that, as a listener at Marino Formenti’s concert, I forget about my everyday life and immerse myself completely in the music, or that I develop an openness and long-term interest in a piece of music that previously meant nothing to me (such as when I choose a piece by certain composers, remember their name, and in the future get to know more pieces).

At the same time, however, a possible alienation is also probable, which manifests itself as an indifference or a repulsion (Rosa 2016, 316; 2017, 319). Perhaps the piece of music I have chosen means nothing to me (I have no relationship with the music), or I want to disrupt or interrupt the piece. It is not about whether I like the piece or not, but whether the piece of music moves me, affects me, and allows me to change (which is also possible through irritation).

Next, I will explain the smallest disc (number 1) at the center of the turntable. Here, four different dimensions of music relationships are distinguished: an intense relationship with objects, ideas, and work; a social interaction with people; an existential relationship to the world; and a self-relationship (Rosa 2016, 73-74; 331; 2017, 321; 2019a). These four dimensions are referred to as relationship to music (as an intense engagement with music, its making, and its challenges), with music (as communal musicking, whether in the form of active music-making, listening, dancing, or other social interactions), in music (as an existential experience of music, where I am seized by its presence without needing to understand the music), and through music (as an experience where new visionary perspectives unfold for me).

If, as an audience member, I am asked by the pianist to turn pages for him, I am in an intense relationship to music, as I need to closely follow the sheet music. If I am engaged in conversation with the pianist or playing four hands with him, I am in a relationship with music. If I am sitting, perhaps with closed eyes, in a deck chair and immerse myself in the music, or if I am lying under the piano and mainly want to experience the sound of the piano in a particularly intense way, I may be in a relationship in music. If listening to the music opens up new thoughts for me and I experience myself as alive and fresh through the music, it is a self-relationship through music.

In relation to the next disc (number 3), I will now address the favorable impulses. Here, many aspects are found that favor a dramaturgy for resonant music relationships, which I adopted throughout my literature study, in particular from publications by theatre scholar Erika Fischer-Lichte (2004; 2012). The mentioned aspects include the core idea, concept, temporality, physicality, spatiality and materiality, as well as risk and possible resistance.

The core idea can be used to ask about the artistic intention and social urgency. In Time to Gather, Marino Formenti is aiming towards his own musical and personal openness (and presumably also towards the openness of his concert attendees). Additionally, he wants to create encounters in the concert and to enable participants to get to know each other.

The concept involves rules that describe the procedure more precisely. In Time to Gather, the rules help to ensure that the desired openness and encounters as envisioned by Formenti can occur, and a change of perspective can take place.

Temporality indicates that the temporal, but also energetic, course of mediation situations (whether it be a concert, a workshop, a podcast, an installation, or another format) must be considered. Where are particularly dense phases? How is the event rhythmized? How are beginnings, transitions, highlights, possible breaks, and conclusions designed? Is time designed as a ritual, and if so, how is this possible in a meaningful and sensual way? When experiencing resonance, time is perceived differently; sometimes one forgets time, sometimes it flies by. In his concept for Time to Gather, Formenti describes time and togetherness as being different and music as flowing accordingly. His concert, as reported in the video, lasts six hours, or until no more music requests are made. This duration is not only a challenge for him as a pianist, but also for the audience (and it is understandable that some of the audience might leave earlier). The duration (chronos) of a mediation event must be suitable for the entire setting; there is no causal rule for this. What seems crucial to me is sensitivity to the right moment (kairos), although this cannot be forced, just as the experience of a perceived eternity (aion) cannot be forced.

Physicality indicates that resonance is a physical phenomenon. All participants must feel physically comfortable and inspired and have the opportunity to participate creatively (even if only in thought). Through the special seating (see the next aspect), Formenti creates a special form of physicality. A visitor in the video mentions that she greatly appreciates listening to music while lying down. However, the duration of the concert also affects physicality. In addition to physical effort or relaxation, movement and dancing are also important aspects that can be considered here. Whether there was dancing in the described concert remains unclear – but it would be possible in principle.

Spatiality and materiality focus attention on the atmospheres, statements, invitations, and challenge (in German: Aufforderung) of the space. How can these be treated, together with the existing materiality? In Time to Gather, the grand piano is at the center of the space; around it are various seating options, such as deck chairs, armchairs, sofas, cushions, and mattresses (especially under the grand piano). Tables with scores are placed on the side. There is no front or back to the room; the circular arrangement creates a sense of connection and mutual visibility. However, the circular arrangement also allows for social control and is thus an exercise of power (Foucault 2016).

Risk and possible resistance are again aspects that favor unavailability and thus liveliness (and prevent manipulation). To what extent do the core idea and its rules allow for risk? What would possible resistances be, and how are they dealt with? In its openness, Formenti’s concept leaves some room for maneuver. However, the setting (the concert took place as part of a festival for contemporary music) suggests that people are willing to engage with the unfamiliar while simultaneously reacting (re-)adaptively. How would Time to Gather work if Formenti were to leave this protected setting? Indeed, Formenti performs in his other performances outside his comfort zone, for example, in public spaces.

Let us now turn to the largest disc (number 4) of the model: here, underlying principles are mentioned, namely meaningfulness and sensuality, perceptibility and accessibility, sensitivity to discrimination, collaboration, mediopassivity, medioordination, and medioconjunctivity.

Resonant music relationships are characterized by meaningfulness and sensuality9. These interactions are full of meaning. On the one hand, they concern our inner convictions: we value the event as important. On the other hand, the event involves our senses, and we are eager to engage with it. The blend of meaningfulness and sensuality generates strong relevance and motivation, indicating that resonance-oriented music mediation integrates both education and enjoyment. In doing so, it overcomes this supposed dichotomy. Formenti states in the video interview that in this concert format, his aim is to work on his own openness, but he wishes the evening to become a party, too. The audience can look at the sheet music or just listen to the music while sitting in a deckchair with a drink in their hand.

The two principles, perceptibility and accessibility, indicate that music mediation must provide a fundamental access to music. So, these two principles relativize a complete uncontrollability of music and resonance to a semi-uncontrollability (Rosa 2018b, 48). To what extent perceptibility and accessibility are given in Formenti’s concert is difficult to assess due to the video. What conditions were created and what resources were provided to ensure accessibility and barrier-free access? How, where, and for whom was the concert advertised? Were there, for example, also affordable tickets? How was it communicated whether and how the building could be reached by people with different disabilities and to what extent were support measures offered? What conditions and resources are necessary for accessibility and barrier-free access?

Correspondingly, the next underlying principle calls for sensitivity to discrimination. Here, questions arise such as: Are one’s own privileges recognized? What preconceptions shape the event? Where do power dynamics emerge, and how are they dealt with? How is the possibility of discrimination and exclusion addressed? How is commitment to equity demonstrated? To what extent are resources handled carefully?

Collaboration is another underlying principle inherent in music mediation (given the very meaning of the term). In the concert, the pianist relies on collaboration with his audience: without their song suggestions, no music is played. Yet within the concept of Time to Gather, Formenti goes even further. The title already indicates that it is about a gathering. In his concept, Formenti writes about a special form of togetherness. Formenti wishes for an audience that listens, plays, and sings with or even instead of him. So, the roles are fluid, as is the case with collaboration, which can sometimes lead to conflicts.

The last three underlying principles consist of mixed ratios. They are mediopassivity, medioordination, and medioconjunctivity. Mediopassivity (Rosa 2019b, 45-46) refers to a simultaneity of activity and passivity, as is the case with perception: I perceive something, so I am active, and at the same time, I am passively affected. Making music, and especially improvising, implies mediopassivity because it requires simultaneous listening and responding. Yet this applies not only to musicians among themselves but also in their relationship with the audience or workshop participants. Resonance arises from interaction, which is why concerts (and all other situations) are not about sender-receiver communication, but about mutual listening and responding. As music mediators and musicians, it is very much about listening (not just affecting people but also enabling their self-efficacy). In the concert Time to Gather, listening and making music are possible both by the pianist and by the audience. First, the pianist listens to the audience and then plays the music suggested.

Medioordination is a term coined by me (Müller-Brozović, 2024). Like an open piano as an ideal resonance space, medioordination describes a simultaneous closeness and openness. The concept of Time to Gather has such clarity and simultaneous flexibility. The idea is simple yet leaves enough room for all involved.

With medioconjunctivity, I mean a binding yet loose form of relationship. Resonant relationships are based on fundamental trust and an orientation towards the common good while allowing individual freedom. The concept of Time to Gather aims for an intensive yet individual form of togetherness. The rules commit to certain behavior yet one can freely decide on it. The pianist extends great trust to the audience and hopes that people will embrace his concept. He also cannot estimate which (musical) actions individual people will bring. All three mixed ratios greatly favor lively music-making and resonant music relationships.

The four discs can be rotated, allowing the aspects to be arranged in different constellations. Time to Gather can, for example, be discussed under the following aspects: How can good conditions be created for relationships in music with self-efficacy, temporality, meaningfulness, and sensuality? It can be assumed that this requires a considerable amount of time, and people themselves want to decide in which seating or lying position they want to immerse themselves in music (or not). Therefore it is advantageous to offer a selection and also to create opportunities for changing location. The concert situation can be charged with significance (e.g. through the uniqueness of being held at a festival or through the communicated laboratory situation, where Formenti wants to test his own openness). At the same time, Formenti’s announcement that it is a party allows for a casual approach to concert conventions and emphasizes the special nature of the event. Ultimately, the listeners can choose for themselves how to behave, thereby experiencing a certain sense of self-efficacy (even if they choose to leave the concert). The example of Time to Gather demonstrates that even if all aspects are present on the turntable, resonance cannot be guaranteed. However, the model can serve as an analytical tool and encourage resonance-oriented approaches during the process of conception, inviting exploration of new, perhaps less considered methods.

The concept of resonance, as understood here, describes the nature of a world relationship and contradicts the everyday understanding of resonance as a metaphor for consonance, harmony, and agreement. This also leads to misunderstandings in the scientific discourse regarding Rosa’s theory of resonance. A major criticism is that resonance cannot be captured with clear indicators, and a simulation of resonance cannot be recognized. Additionally, Rosa is criticized for overlooking structural problems in his theory of resonance (Rosa 2018a).

My own criticism of the theory of resonance focuses on the many musical examples that Rosa uses in his publications. Often, these examples correspond more to a synchronous resonance (e.g. the vibration of two tuning forks at the same frequency) or musical nostalgia for one’s favorite music (Rosa 2016, 211-212; 523). Rosa seems to have an indifferent relationship to contemporary music, as he particularly denies affective and effective power to atonal music (Rosa 2016, 499-500). Moreover, it is surprising that, as a sociologist, Rosa does not address the potential for distinction in music and only marginally touches on its manipulative danger (Rosa 2016, 370). In contrast or extension to Rosa, the present theoretical foundation of music mediation incorporates a possible alienation as one of the defining characteristics of resonance. The fact that just one year after the publication of Rosa’s theory of resonance, a volume of criticism (Peters & Schulz 2017) was published, in which Rosa himself wrote a response, demonstrates how strongly this theory has been received and discussed. There are also several publications in the German-speaking field of music education on Rosa’s theory of resonance (Oberschmidt 2019; Koch and Niegot 2020; Schatt 2020a), which align with the aforementioned criticism, but also recognize resonance as a designation of musical quality (Mahlert 2020) and attribute to it a potential for a musical turn in cultural studies (Schatt 2020b, 201).

The model of resonance-oriented music mediation aims to foster the creation, deepening, and broadening of music relationships, and can be used for conceiving and analyzing music mediation projects. Resonance is defined as a vibrant interaction with the following characteristics: affection, self-efficacy, uncontrollability, transformation, and a possible alienation. Furthermore, the model includes four dimensions of resonant music relationships, suggests favorable impulses and describes underlying principles.

Recognizing that resonance can only be facilitated, the approach views music mediation as an open-ended process that transforms all participants, including the musicians and institutions. This approach acknowledges the inherent risks, including the possibilitites of resistance and alienation. Based on the assumption that resonance is a responsive process of different voices, the following ethics of resonance emerges:

For in contrast to an echo, which is hearing your own sound or voice thrown back at you by some obstacle, resonance is an answer by a different voice, in a different tone or frequency. This necessarily implies difference. We can only get in resonance with something or someone out there that is insurmountably different from us and non-controllable. Therefore, it is not about the “nostrification” of another, and not about the reinforcement of one’s identity, but about its transformation. (Rosa 2020, 399)

Therefore, resonance-oriented music mediation rejects traditional expectations, such as cultivating a particular taste in music or building a future audience. Instead, it advocates strong experiences with music, whether in new or traditional concert formats, in communities, in the media or in other areas. With its wide-ranging approach, resonance-oriented music mediation opens up a broad and dynamic field for practice and research. Future work could examine its application in different musical and cultural contexts, and thus possibly enrich our musical practices in society.

Having grown up stateless myself in my early childhood, I have a personal connection to the problematic nature of the term ‘citizenship’. I try to be as sensitive as possible to the privileges and exclusions associated with citizenship. Moreover, the term ‘artistic’ is a problematic one, too (Garcia-Cuesta 2024, 82; 85). With this in mind, I strive to use music as a co-creative means to further a movement of social responsibility towards responsability and to contribute to the common good by promoting strong experiences involving music.↩︎

I live in the German-speaking cultural area, which has influenced the content of this contribution.↩︎

In addition, Western art music is also associated with Eurocentrism. Resonance-oriented music mediation therefore demands critical self-reflection and a sensitivity to discrimination.↩︎

Cultural participation is mentioned in Article 27 [1] of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. www.ohchr.org/en/human-rights/universal-declaration/translations/english (accessed October 30, 2024).↩︎

3 Music sociologist Antoine Hennion (2015) presents a sociology of mediation in his book The Passion for Music, too. He emphasizes the aspect of taste and focuses on the reception of works. The resonance-oriented music mediation discussed here, however, does not aim to educate taste and is situated in a broader area that extends far beyond the reception of music. In a fundamental way, resonance-oriented music mediation draws on John Dewey (1934), who conceives of art as experience in everyday life. Alfred Schütz’s (2015) sociological studies on music-making are also important for the present research. Furthermore, Tia De Nora’s work on music in everyday life (DeNora 2000) and well-being (Ansdell and DeNora 2016) should be emphasized.↩︎

marinoformenti.net/time-to-gather (accessed May 27, 2024).↩︎

marinoformenti.net/time-to-gather (accessed May 27, 2024).↩︎

In contrast to Hartmut Rosa, who defines resonance only in terms of the first four aspects, I believe that resonance can only arise against the background of a possible alienation, which is why I include this fifth defining aspect. Resonance is not a permanent phenomenon. It can always withdraw. This fact explains the paradox that possible alienation, as the opposite of resonance, is at the same time a precondition for resonance. In addition, a possible alienation prevents the danger of manipulation.↩︎

This term is not meant in a sexual sense.↩︎

Ansdell, Gary, and Tia DeNora. 2016. Musical Pathways in Recovery. Community Music Therapy and Mental Wellbeing. London: Routledge.

Born, Georgina. 2005. “On Musical Mediation: Ontology, Technology and Creativity”. twentieth-century music 2, no. 1: 7-36.

———. 2015. “Mediation Theory”. In The Routledge Reader on the Sociology of Music, edited by John Shepherd and Kyle Devine, 359-367. New York: Routledge.

Bradley, Deborah. 2018. “Artistic citizenship: Escaping the violence of the normative(?)”. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 17, no. 2: 71-91. DOI: 10.22176/act17.1.71.

Carson, Charles and Maria Westvall. 2024. “Art for All’s Sake: Co-Creation, ‘Artizenship’, and Negotiated Practices”. In Music as Agency. Diversities of Perspectives on Artistic Citizenship, edited by Maria Wetvall and Emily Achieng' Akuno, 8-18. New York: Routledge.

Cook, Nicholas. 2013. Beyond the Score. Music as Performance. New York, Oxford, Auckland: Oxford University Press.

DeNora, Tia. 2000. Music in Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dewey, John. 2005. (1934). Art as Experience. New York: Perigee.

Elliott, David James, Marissa Silverman and Wayne D Bowman. 2016. Artistic Citizenship. Artistry, Social Responsibility, and Ethical Praxis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika. 2004. Ästhetik des Performativen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

———. 2012. Performativität. Eine Einführung. Bielefeld: transcript.

Foucault, Michel. 2016. Überwachen und Strafen. Die Geburt des Gefängnisses. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Gabrielsson, Alf. 2011. Strong Experiences with Music. Music is Much More than Just Music. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Garcia-Cuesta, Sergio. 2024. “Listening all around: What could the fluid conceptualization of artistic citizenships do?” Action Criticism and Theory for Music Education 23, no. 1: 80-101. DOI: 10.22176/act23.1.80.

Gaunt, Helena, Celia Duffy, Ana Čorić, Isabel R. González Delgado, Linda Messas, Oleksandr Pryimenko and Henrik Sveidahl. 2021. “Musicians as ‘Makers in Society’: A Conceptual Foundation for Contemporary Professional Higher Music Education”. Frontiers in Psychology 12, (713648): 1-20. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713648.

Hennion, Antoine. 2015. The Passion for Music. New York: Ashgate/Routledge.

Hornberger, Barbara. 2020. “Was wir uns ein-bilden. Musikpädagogik aus der Perspektive der Cultural Studies”. In Vorzeichenwechsel. Gesellschaftspolitische Dimensionen von Musikpädagogik heute, edited by Ivo Ignaz Berg, Hannah Lindmaier and Peter Röbke, 47-64. Münster, New York: Waxmann.

Koch, Jan-Peter and Adrian Niegot. 2020. “Von responsiven und repulsiven Beziehungen: Resonanz – gelingendes Leben – Musikpädagogik”. In Gelingendes Leben und Musik, edited by Adrian Niegot, Constanze Rora and Andrea Welte, 213-222. Düren: Shaker.

Krupp-Schleußner, Valerie. 2016a. “Der Capability Approach in der musikpädagogischen Teilhabeforschung. Empirische Anwendung eines capability-basierten Modells der Teilhabe an Musikkultur”. Beiträge empirischer Musikpädagogik 7, no. 1: 1-28. Accessed October 30, 2024. bem.journals.qucosa.de/bem/article/view/140/285.

———. 2016b. Jedem Kind ein Instrument? Teilhabe an Musikkultur vor dem Hintergrund des capability approach. Münster: Waxmann.

Leech-Wilkinson, Daniel. 2020. Challenging Performance: Classical Music Performance Norms and How to Escape Them. Version 2.2.2. Accessed October 30, 2024. challengingperformance.com/the-book.

Mahlert, Ulrich. 2020. “Gelingende Weltbeziehungen. Musikpädagogische Überlegungen zu Hartmut Rosas Theorie der Resonanz”. In Musik und Ethik. Ansätze aus Musikpädagogik, Philosophie und Neurowissenschaft, edited by Katharina Bradler and Annemarie Michel, 137-144. Münster: Waxmann.

Müller-Brozović, Irena. 2017. “Musikvermittlung”. KULTURELLE BILDUNG ONLINE. www.kubi-online.de/artikel/musikvermittlung. DOI: 10.25529/92552.351.

———. 2018. “Von der Arena zum Forum. Unterschiedliche Spielformen in Musikvermittlungsprojekten”. In Zusammenspiel? Musikprojekte an der Schnittstelle von Kultur- und Bildungseinrichtungen, edited by Johannes Voit, 30-47, Hamburg: Hildegard Junker.

———. 2023a. “Resonanzaffine Musikvermittlung. Ein dynamisches Modell für starke Musikerlebnisse”. In 44. Jahresband des Arbeitskreises Musikpädagogische Forschung, edited by Michael Göllner, Johann Honnens, Valerie Krupp, Lina Oravec and Silke Schmid, 195-212. Münster: Waxmann.

———. 2023b. “Curating Resonances through Creating Relationships”. oncurating 57, No Cure: Curating Musical Practices, edited by Anja Wernicke and Michael Kunkel. Accessed May 24, 2024. https://www.on-curating.org/issue-57-reader/curating-resonances-through-creating-relationships.html.

———. 2024. Das Konzert als Resonanzraum. Resonanzaffine Musikvermittlung durch intensives Erleben und Involviertsein. Bielefeld: transcript.

Oberschmidt, Jürgen. 2019. “Den Resonanzdraht in Schwingung versetzen. Eine Auseinandersetzung mit Hartmut Rosas Soziologie der Weltbeziehung in musikpädagogischer Absicht”. Diskussion Musikpädagogik 81, 14-20.

Peters, Christian Helge and Peter Schulz, eds. 2017. Resonanzen und Dissonanzen. Hartmut Rosas kritische Theorie in der Diskussion. Bielefeld: transcript.

Petri-Preis, Axel, and Johannes Voit, eds. 2023. Handbuch Musikvermittlung Musikvermittlung – Studium, Lehre, Berufspraxis. Bielefeld: transcript.

Rosa, Hartmut. 2013. Beschleunigung und Entfremdung. Entwurf einer kritischen Theorie spätmoderner Zeitlichkeit. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

———. 2016. Resonanz. Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

———. 2017. “Für eine affirmative Revolution. Eine Antwort auf meine Kritiker_innen”. In Resonanzen und Dissonanzen. Hartmut Rosas kritische Theorie in der Diskussion, edited by Christian Helge Peters and Peter Schulz, 311-329. Bielefeld: transcript.

———. 2018a. “Response: Resonanz. Rhetorischer Wettstreit des Debattierclubs Streitpunkt der Universität Leipzig”. Accessed May 27, 2024. www.youtube.com/watch?v=SC-NzyAihpk.

———. 2018b. Unverfügbarkeit. Wien, Salzburg: Residenz.

———. 2019a. “Musik als zentrale Resonanzsphäre. Presentation at the Congress of Verband deutscher Musikschulen”. Accessed May 27, 2024. www.musikschulen.de/medien/doks/mk19/dokumentation/plenum-1_rosa.pdf.

———. 2019b. “Spirituelle Abhängigkeitserklärung. Die Idee des Mediopassiv als Ausgangspunkt einer radikalen Transformation”. In Große Transformation? Zur Zukunft moderner Gesellschaften, edited by Klaus Dörre, Hartmut Rosa and Karina Becker, 35-55. Wiesbaden: Springer.

———. 2020. “Beethoven, the Sailor, the Boy and the Nazi. A reply to my ritics”. Journal of Political Power 13, no. 3: 397-414. DOI: 10.1080/2158379X.2020.1831057.

Schatt, Peter W. 2020a. “Musikalische Praxis als Teilhabe am ‘immateriellen kulturellen Erbe’ – ein Weg zum gelingenden Leben? Probleme und Perspektiven im Kontext kultureller Diversität”. In Gelingendes Leben und Musik, edited by Adrian Niegot, Constanze Rora and Andrea Welte, 28-48. Düren: Shaker.

———. 2020b. “turn-Übungen? Kulturelle Bildung im Lehramtsstudium Musik”. In Musik – Raum – Sozialität, edited by Peter W. Schatt, 201-209. Münster: Waxmann.

Schmid, Silke. 2014. Dimensionen des Musikerlebens von Kindern. Theoretische und empirische Studie im Rahmen eines Opernvermittlungsprojektes. Augsburg: Wißner.

Schütz, Alfred. 2015. “Making Music Together. A study in Social Relationship”. In The Routledge reader on the sociology of music, edited by John Shepherd and Kyle Devine, 57-65. New York: Routledge.

Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking. The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Hanover, N.H.: Wesleyan University Press.

Irena Müller-Brozović is a Professor of Music Mediation at Bruckner University in Linz (Austria) and at the Bern Academy of the Arts (Switzerland). She co-directs the Forum Musikvermittlung, a network for German-speaking music universities, and serves as co-editor of the International Journal of Music Mediation. She completed her studies in piano, school music, and music mediation in Basel, Detmold, and Vienna. Her teaching and research draw on extensive experience as a music mediator for orchestras and festivals.

ISSN 2943-6109 – Volume 1 (2024) – DOI: 10.71228/ijmm.2024.9

This paper is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Parts of an article may be published under a different license. If this is the case, these parts are clearly marked as such.