Building on the research of Octobre and Patureau (2018), this article invites reflection on the treatment of gender issues in digital mediation formats developed by music mediation organizations and concert promoters. Studies in the sociology of artistic work (Coulangeon and Ravet 2003; Buscatto 2007; Bousquet et al. 2018) consistently show that music fields – be it classical, jazz, or pop – are affected by a dual gender segregation: horizontal (gender distribution based on the type of employment) and vertical (lower access to leadership positions). One might assume that producers of digital mediation formats, who advocate for values such as coexistence, social inclusion, and agency (Perez-Roux and Montandon 2014; Carrel 2017), and who are aware of the normative and prescriptive effects of educational resources (Octobre 2014), would question these boundaries. The ‘counting’ and analysis of ‘cases’ derived from the systematic examination of approximately one hundred accessible online digital formats produced by music production and dissemination organizations will demonstrate that this is not the case.

Dans le sillage de l’ouvrage dirigé par Octobre et Patureau (Octobre et Patureau 2018), cet article engage à une réflexion sur le traitement de la question du genre dans les dispositifs numériques de médiation produits par des organismes de diffusion et de production musicale. Les études en sociologie du travail artistique (Coulangeon et Ravet 2003; Buscatto 2007; Bousquet et al. 2018) ne cessent de montrer que l’ensemble des mondes de la musique, aussi bien classiques que jazz ou pop, est traversé par une double ségrégation genrée horizontale (répartition sexuée selon le type d’emploi) et verticale (moindre accès aux postes à responsabilités). On pourrait imaginer que les producteurs de dispositifs numériques de médiation de la musique, portant des valeurs de vivre-ensemble, d’inclusion sociale et d’agentivité (Perez-Roux et Montandon 2014; Carrel 2017), et conscients des effets normatifs et prescriptif des supports éducationnels (Octobre 2014), viennent questionner ces frontières. Le « dénombrement » et l’analyse de « cas » tirés du dépouillement systématique d’une centaine dispositifs numériques consultables en ligne et produits par des organismes de production et de diffusion musicale permettront de montrer que tel n’est pas le cas.

Im Anschluss an die Forschung von Octobre und Patureau (Octobre und Patureau 2018) regt dieser Artikel zu einer Reflexion über den Umgang mit der Geschlechterfrage in digitalen Vermittlungsformaten an, die von Musikvermittlungsorganisationen und Konzertveranstaltern entwickelt wurden. Studien zur Soziologie der künstlerischen Arbeit (Coulangeon und Ravet 2003; Buscatto 2007; Bousquet et al. 2018) zeigen immer wieder, dass die Musikbereiche – sowohl klassische als auch Jazz- und Popmusik – von einer doppelten geschlechtsspezifischen Segregation betroffen sind: einer horizontalen (geschlechtliche Verteilung je nach Art der Beschäftigung) und einer vertikalen (geringerer Zugang zu Führungspositionen). Man könnte annehmen, dass die Produzenten digitaler Vermittlungsformate, die Werte wie Zusammenleben, soziale Inklusion und Handlungsfähigkeit vertreten (Perez-Roux und Montandon 2014; Carrel 2017), und sich der normativen und präskriptiven Wirkung von Bildungsressourcen bewusst sind (Octobre 2014), diese Grenzen hinterfragen. Die „Zählung“ und Analyse von „Fällen“, die aus der systematischen Auswertung von rund hundert online zugänglichen digitalen Formaten stammen werden zeigen, dass dem nicht so ist.

Cultural mediation, digital, music, gendered stereotypes, gender relations

Since the early 2000s, music institutions have been throwing themselves into the production of digital cultural mediation devices that, in music, can take on various forms, from the least interactive video clips2to the most immersive vidéo 360°3, along with gaming platforms4, podcasts5, listening guides6, and more. These digital music mediation devices represent a “burgeoning resource” (to paraphrase what is stated in Quebec’s policies on educational success [Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignement supérieur 2017, 60]) which, in Quebec, is due to the sharp increase in digital development plans7, as well as the growing number of training programs organized by professional orders for their members. Thus, in 2017-2018, the Conseil Québécois de la Musique (CQM) established leadership cohorts (Cohorte Leadership numérique [CQM 2017]) for reflecting on how digital technologies are used in cultural mediation in music and in training courses in the field (Grand Rendez-vous de la musique [CQM 2019]). Many organizations consider that “the capacity of institutions to be in sync with contemporary society” (Beudon 2014) depends on their ability to go digital. This belief is connected to their growing interest in music mediation (Kirchberg 2020).

Following in the footsteps of museums (Montpetit in Casemajor et al. 2017), classical music institutions have initiated a change of direction aimed at opening their premises to audiences with more diverse socio-demographic profiles than those repeatedly identified in sociological surveys. The average age of the classical music audience is over 60, with high levels of educational and economic capital (Dorin 2018; Donnat 2010). With this aim as a starting point, Quebec’s musical community, which had already developed arts education initiatives, shifted its interest to cultural mediation. As is often the case when the term mediation is introduced into cultural institutions (Lussier 2015), these organizations initially grasped the audience development potential of this practice, closely associating it with their programming and its dissemination (Kirchberg 2018). At first, these institutions favoured hermeneutic mediation (Lacerte 2007) in which mediators acted as interpreters to pass on knowledge about the works.

In Quebec (Kirchberg 2018) as in France (Pébrier 2020), music production and dissemination organizations have thus tended to link mediation to teaching, in an institutional understanding of cultural mediation, associating it closely with goals of knowledge transfer (Kirchberg and Duchesneau 2020; Beauchemin, Maignien, and Dugay 2020). More recently, the civic aspect of mediation has penetrated institutions and become associated with notions of social inclusion and equity. In this sense, mediation also refers to:

[…] creating spaces where audiences feel respected and seen for their differences, first and foremost for the attention paid to them and for the hospitality shown by the institution that welcomes them, that seeks to explain, to inform, to translate. [...] This implies creating spaces for encounters between the audience and the work, the audience and the cultural institution, the audience and other visitors. In short, it means ensuring that these cultural venues are also public spaces (Rasse 2001, 75)

Concerns about everyone (no matter their background, gender, physical condition, skin colour, language, sexual orientation, etc.) being able to participate in cultural life have now come to be closely associated with music mediation initiatives.

Therefore, cultural mediation within music organizations sits at the crossroads of performing and/or introducing the works inspired by so-called active teaching approaches, and projects promoting values of otherness, social inclusion, and participant empowerment (Kirchberg 2020). It can thus be concluded that, in the context of mediation activities, music institutions present themselves as agents of transformation of the power relations in society. What, then, of the way in which gender relations are dealt with in the classical music world today, and more specifically, in the digital devices for music mediation?

Studies on cultural practices in France and Quebec show a constant feminization of amateur musical practices. Women attend music institutions more frequently (Donnat 2005), are more involved in amateur instrumental practice (Octobre 2005), and play a central role in the transmission of artistic practices within the family. Yet studies in the sociology of arts work (Coulangeon and Ravet 2003; Buscatto 2007; Bousquet et al. 2018) constantly show that a double segregation, horizontal and vertical, spans the whole music world, whether classical, jazz, or pop. Thus the music milieu “helps produce and legitimize the gendered hierarchies at work in Western societies” (Buscatto 2016).8

One could well imagine that producers of digital devices for music mediation, with their values of social coexistence (le vivre-ensemble), social inclusion, and agency (Perez-Roux and Montandon 2014; Carrel 2017), conscious as they are of the normative and prescriptive effects of educational media (Octobre 2014), would question these social gender relations in the music milieu. Following the example of articles listed in the books Normes de genre dans les institutions culturelles and Sexe et genre des mondes culturels, collected by Octobre and Patureau (Octobre and Patureau 2018; Octobre and Patureau 2020), this text offers a reflection on how the gender question is dealt with in the digital devices designed for music mediation by music production and dissemination organizations.

From a Foucauldian perspective, these digital mediation media must be considered “a resolutely heterogeneous arrangement of statements and visibilities that itself is a result of involving a set of means called upon to function strategically within a given situation or force-field (Vouilloux 2008, 15-31). This article aims to show how gender relations at play in the music world are embedded in digital interfaces, based on appropriation and partial restitution of knowledge about music. We hypothesize that power dynamics based on gender relations are embodied in the arrangement of the images, vocabulary, and musical excerpts that make up these devices. What are the gendered representations of the music world within which users of these are obliged to evolve because of how these digital music mediation devices – fundamental forms of “knowledge-power” – are structured? As Foucault wrote in 1972:

Power relations (with the struggles that pervade them or the institutions that maintain them) do not simply facilitate or hinder knowledge; they do not merely favour or stimulate it, distort or limit it; power and knowledge are not linked to each other by the mere interplay of interests or ideologies; therefore, the problem is not simply to determine how power subordinates knowledge and makes it serve its own ends, or how power superimposes itself on knowledge and imposes ideological content and limitations. No knowledge is formed without a system of communication, recording, accumulation, and displacement, which is itself a form of power and is linked, in its existence and functioning, to other forms of power. Conversely, power is not exercised without the extraction, appropriation, distribution, or retention of knowledge. On this level, there is not knowledge on one side and society on the other, or science versus the state, but only the fundamental forms of “knowledge-power”. (Foucault 1972, 283)

In a 2018 article, Samuel Chagnard conducted a case study based on the section of the Orchestre de Paris website specifically targeted at “adults who are simply music lovers or even complete neophytes, who want to understand a little about what makes an orchestra” (Chagnard 2018). His investigation of social gender relations shows how the intentions behind a mediation activity can be usurped by the device put in place, thus reinforcing the very social representations meant to be changed. Based on a content analysis of 152 digital music mediation devices (see methodology), we set out to answer this question: are the digital music mediation devices produced by music dissemination and production organizations gender neutral? What do they reveal about the world of music?

This article draws from work begun in spring 2018 by the Music Mediation Partnership Study (P²M), in close collaboration with the Conseil Québécois de la Musique. By adopting an inductive approach that stems from an analysis of the productions available on the internet, our team’s goal was to offer a description of the digital music mediation devices used by music producers and disseminators. Michel Duchesneau and Irina Kirchberg, respectively professor and invited professor at the Université de Montréal’s Faculty of Music, conducted this research in the context of receiving SSHRC Partnership Engage funding. Research assistants Justin Bernard, Elsa Fortant, Pierre-Luc Moreau, Heloïse Rouleau participated in developing the analysis grid applied to the devices and completed the painstaking work of collecting and studying the devices. Our thanks to all of them.

Due to the language skills of the team members working on this project, the study intentionally focuses on devices produced in France, Canada and Germany by production or dissemination organizations. Between 2018 and 2020, we have therefore systematically examined the platforms of such organizations, the lists of which have been drawn up on the basis of consultations with national orchestra associations and musicians’ rights organizations. In September 2020, the critical repertoire of digital mediation devices compiled on the basis of this research totaled 261 devices. The analyses presented in this article are based on the enumeration, systematic analysis, and study of ‘cases’ drawn from the 152 digital devices designed by organizations producing and disseminating mainly ‘classical’ musical repertoires (and excluding devices created by educational institutions or individuals).

The limits of our corpus, as well as the analysis grid applied to it, are made clear by the three terms used in the title of this research project, namely “digital” “devices” for “music mediation”. Firstly, the term “device” expresses the ‘means to an end’ of an apparatus, in other words within an environment where prescription and latitude meet. The criteria for considering a device digital have been limited to considering any device available on the web that is not wholly printable and whose transformation into a physical format would not limit the use of any of its components. Websites and applications were included in our study, but not off-line devices. Therefore, educational guides published online in PDF format do not meet this definition of a “digital device” and are not included in the corpus presented here. Secondly, given the vast scholarly differences in how cultural mediation is understood, our team decided that the devices linked to concert promotion – in our view closer to communications or publicity – or the online publishing of documents illustrating an activity being carried out online – considered to be archival or associated with promoting the brand of the institutions in question – would not be included in the corpus, because they did not reveal a cultural mediation process as defined at the beginning of this article. Lastly, all the digital devices listed refer to music as a “total musical fact" (Green 2006). This clarification draws attention to the fact that these digital devices are not based solely on presenting the structural components of the music analyzed (akin to what we call “music theory”), but also on exploring repertoires by approaching, among other things, the works’ associated sociocultural, political, economic, and historical contexts.

Each device that met these three criteria was subjected to an analysis grid of 70 questions (multiple choice, either preformed or open), divided into nine main categories. This analysis grid was used to critically think through our corpus, built with a MySQL database using the Django platform to integrate descriptive sheets for each device identified. The critical catalogue of digital music mediation devices compiled on the basis of these data sheets collates information on the form, content, access mode, production costs, and production schedule of such systems, among other things. The choice was made to base the analyses on a French-language bibliography rooted in sociology and devoted to the analysis of gendered discrimination in the world of culture and, more specifically, music.

Analysis of these digital devices for music mediation shows that most contribute to downplaying the presence of women in the music world. There are more than twice as many devices featuring no female characters (people, animals, anthropomorphic instruments) than there are with no male characters (65 devices with no women, 30 devices with no men).9

There are many more men and male characters in these digital devices than women and female characters, or characters whose gender is not set by gendered traits. Within the corpus, there are 379 characters who are men, compared to 291 who are women, and just 19 whose gender cannot be determined (see Table 1). This under-representation is similar in terms of drawn characters (people, animals, and anthropomorphic instruments) whose gender is indicated by adding gendered traits (215 animals and anthropomorphic instruments associated with male gender compared to 84 associated with female gender, and 69 of unspecified gender).

| Female gendered traits | Male gendered traits | No gendered traits | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humans on screen | 291 | 379 | 19 | 689 |

| Drawn characters (anthopomorphic people, animals and instruments) | 84 | 215 | 69 | 368 |

| TOTAL | 375 | 594 | 88 | 1057 |

These digital mediation devices digitally reproduce an already widely-analyzed initial mechanism for ousting women from the arts world. In her 2019 article devoted to music teaching manuals, Caroline Ledru shows that it is still possible in the 21st century to complete an entire musical education while totally ignoring female creators (Ledru 2019). In the digital mediation devices observed in this study, the music world finds itself once again mostly cut off from the presence of women.

An analysis of the male/female breakdown of the top ten on-screen functions featured in digital mediation devices confirms that male representation dominates (see Table 2).

Cultural mediators and narrators are mainly men. This is even more true given that the numbers conceal a much more unbalanced male/female distribution than the ratio of one female mediator to two male mediators. The visibility of on-screen female mediators is in fact solely due to the figure of Camille Villanove (and her three series Allez raconte, Camille! and Melomaniac), while Clément Lebrun, Xavier Rockenstrocly, Yan England, Patrice Belanger, Bernard Chapelle, and others share the screen on the male mediator side (P²M and CQM 2019).

| Actors | Women | Men | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural mediator | 20 | 44 | 64 |

| Instrumentalist | 28 | 29 | 57 |

| Conductor | 18 | 17 | 35 |

| Singer | 17 | 7 | 24 |

| Composer | 0 | 22 | 22 |

| Personalities featured on screen | 114 | 164 | 307 |

Musical life is thus deciphered and recounted in these digital mediation devices by a man’s “voice/approach”.10 What’s more, the data shows that the predominance of men is not achieved in the same way depending on the music professions featured. Prestigious professions “become masculine” (Détrez and Piluso 2014, 30) and the others typically become feminine. Women embody nearly three out of four singers, while none of the women featured on screen is a composer.11 When composer John Rea is invited to talk about the decisive encounters of his career in a clip where the names and photos of these mentors are inserted, only “this other woman composer... well, artist” (SMCQ 2015) is mentioned, but she remains anonymous and faceless (unlike, for example, “the great Canadian composer John Weinzweig”). Merely mentioning the names of female creators remains difficult. While Handel, Mozart, Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Britten, and Moneim are all represented in the Opera Play application (Opera Play 2018), only Ana Sokolović is mentioned.12 Similarly, in another device, to illustrate the process of variation13, a mediator lists the names of authors (Queneau), visual artists (Warhol), and composers (Beethoven, Bach, Debussy) without ever naming a single woman.

And what of conductors? Those familiar with Hyacinthe Ravet’s work (Ravet 2015; 2016) might be surprised by the apparent parity illustrated by Table 8. Once again, these numbers are nothing more than a distortion created by the dynamism of pioneering women (conductors or assistant conductors) who make their own series of devices. Insula Orchestra’s conductor, Laurence Equilbey, is featured in 16 of the 18 devices featuring female conductor characters. The conductor is an important protagonist in the Log Book / Journal de bord14. The same willingness can be seen in Dina Gilbert, who is present in 6 out of 7 devices featuring women assistant conductors15. The role of conductor is so much more systematically embodied by men that in the Petit guide du spectateur16 produced by the Insula Orchestra, the conductor is presented as a man (see Figure 1), even though, as just mentioned, the orchestra’s own conductor is Laurence Equilbey, a woman17.

Similarly, there are no women conductors alongside Alan Gilbert19, François-Xavier Roth20, Matthias Pintscher21, Tito Ceccherini22, Richard Eggar23 at the helm of the concert recordings used in the digital guides produced by the Ensemble Intercontemporain or the Philharmonie de Paris. In other devices, even the small anthropomorphic animals that are supposed to embody the role of leaders find themselves with traits typically associated with the male gender. The interactive Opera Maker provides a striking example. This application allows players to embody and customize the clothing of opera characters, regardless of their gender (swords, skirts, tiaras, armour). The penguin conductor, who will guide the participants through the game, is the only character who cannot be customized, and is equipped with a bow tie to affirm he is male (see Figure 2).

This digital device for music mediation reproduces an unrecognized aspect of gendered vertical segregation in which the position of conductor, a position of prestige (Ravet 2016), remains inaccessible to women. Hyacinthe Ravet pointed out that in France, in 2015, there were no women conductors in permanent symphony orchestras (Ravet 2016). The efforts made by the pioneers to make their profession visible through the production of digital mediation devices have not been sufficient to counterbalance the vertical segregations widely observed in the professional music world. These are insidiously replayed on the digital music mediation stage.

In moments when these digital devices are not contributing to invisibilizing the presence of women listeners, patrons, performers, and composers, and not participating in making us forget women’s constant historical presence within musical worlds (Giron-Panel et al. 2015), women are sometimes alluded to using archaic and androcentric representations that double down on visual and narrative effects.25 These women appear on screen under the pretext of their status as “wives of” or as mothers. The video clips produced by Avner and described as “adaptations of real events”26 leave little room for Anna Magdalena Bach. The latter is presented as “Bach’s second wife”, but her very probable authorship of the works attributed to her husband is passed over in silence. In this series of videos, Constance Mozart is married “somewhat against her will” to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who essentially wants to “frolic”. In the Brahms clip “Allez raconte, Camille! #Bonheur”27, when Clara Schuman is mentioned, she is introduced by the following question from the clip’s male co-host: “Say, she wasn’t fooling around with Brahms, was she?” Although the female co-presenter responds by taking offence at this comment, it’s not to bring up how this internationally renowned artist’s skills have been forgotten, but rather in the following way: “Wait now, look how you’re talking about Schumann’s wife!”. Clara Schumann the internationally renowned composer and performer would never have been presented in this way, and her role in music history is downplayed by her sole assignment to the status of unconditional supporter of Brahms.

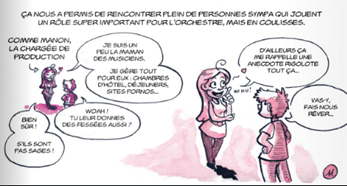

How women are alluded to in digital music mediation devices goes beyond merely minimizing the roles given to them. These women, who are predominantly portrayed as white and curvaceous with long hair, are also reduced to the archetype of the sexualized, submissive woman-object by the convergence of the visual elements and the narrative. This is especially true for ABD à la Philharmonie de Paris28. While the comic strip’s presentation of the workings of an orchestra raises readers’ awareness of gender equality, one of the story’s protagonists, a production manager named Manon with long, flowing hair, short skirt, and fishnet stockings, is subjected to sexual harassment, which is not denounced by the comic strip’s authors (see Figure 3).29

The same mechanism of doubling image and text is at work in the presentation of the synopsis of Mozart’s Don Juan in “Don Giovanni vu par ICI ARTV”31. In Da Ponte’s original libretto, set to music by Mozart, Don Juan attempts to rape Anna in the very first minutes of the opera. In this digital mediation device, Don Juan appears in dark glasses and with a dazzling smile (see Figure 4). We are introduced to him as “the greatest ladies’ man of all time”. Anna, the victim of his first rape, is portrayed with her luscious lips puckered in a pout and a knowing wink in a suggestive pose. As the narrator (a man!) states, here we have “a young woman to seduce”. It is difficult to imagine that the creators of this video clip were unaware of both the work’s dramatic motivations and this historical fact: at its premiere in Prague in 1787, Don Juan was initially described as a “degenerate” who should be “punished” – the opera’s original title was “The Punished Degenerate or the Don Juan” (Clément 1979).

Digital mediation devices are catalysts for this invisible process, which reproduces gendered segregations. There are also recurring symbolic oppositions between devices, reflecting historically, culturally, and socially constructed representations that assign a gender to the instruments (Ravet 2011). Samuel Chagnard (2018) observed, regarding the only device produced by the Orchestre National d'Ile de France, that these contrasts between male and female instruments were based on representations of the instrumentalists’ bodies, clothing, and stereotyped postures. Systematic analysis of the hundred or so devices in our corpus reveals a gendering of the instruments through their anthropomorphization and the evocation of their timbres.

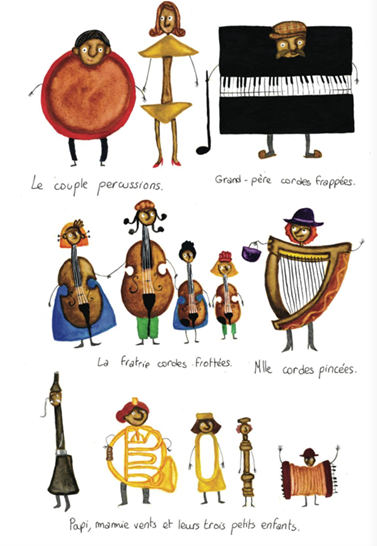

Instrument anthropomorphization is accompanied by an over-representation of gendered attributes. In Petit guide du spectateur33, for example, the harp is equipped with a small purple handbag, which graphic animation makes “her” shake continuously (see Figure 5). To fully grasp the gendering mechanism at work, it’s important to note that it has nothing to do with the French grammatical gender of the instruments represented. The bass drum (feminine word) becomes the (male) partner of a cymbal whose femininity is asserted by a hairstyle, heeled shoes, and a sculpted waistline. The same process applies to the horn and bassoon, both masculine words in French, that become the grandmother (horn) and the grandfather (bassoon) of this instrument family. It is also noteworthy that the family model proposed in these representations is that of a heterosexual family.

Here, instrument registers are used to replicate the gendered split between “masculine/bass” and “feminine/treble” (Monnot 2012, 54). The same mechanism is at play when it comes to the “pitches of notes” in the clip Les éléments invisibles35 produced by the OSM. To substantiate the gendered pitch of notes, the low notes, rendered masculine, are illustrated by the trombone, played by a man. On the other hand, the middle and high notes – more associated with the feminine – are respectively illustrated by a violin and a flute, instruments also considered feminine, played here by two women. Here, instruments and timbres are associated with the gender of their performer. There are other examples of how these representations can be deconstructed, and the trombone mentioned in the example above can be brought up again. For instance, a BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra video about the trombone36 shows two children learning to play the instrument, a girl and a boy, thus thwarting the stereotype of a strictly male instrument and presenting a more gender-neutral image of the trombone. Similarly, Opéra Play37 is an entertaining app that allows users to familiarize themselves with vocal timbres, but avoids the pitfall of gendered attribution by asking that these timbres be associated with asexual shapes (see Figure 6).

After our study of these 152 digital music mediation devices produced by classical music institutions, we can generalize the observation made by Samuel Chagnard at the end of his case study. We are indeed faced with “a kind of stumbling block in mediation, or at least an area of weakness: the reinforcement of a representation that we wish to change” (Chagnard 2018). The digital music mediation devices created and/or disseminated by these cultural institutions that produce or disseminate music are more a reflection of the gender relations at work in professional worlds than they are drivers of transformation (Octobre and Patureau 2018). In these digital devices for mediating music, mechanisms for producing and reproducing discrimination, exclusion, differentiation between men and women, and sometimes even the insidious disqualification of the latter, are obviously and naturally exposed.

On the one hand, we are witnessing an invisibilization of women in the music business that contributes to “normalizing their absence” (Détrez and Piluso 2014, 31). Female composers, conductors, and others are not mentioned, and the reasons for their absence in these digital music mediation devices are not made explicit. The mechanisms by which women are ousted from the history of music, in which “oblivion itself is forgotten”, are thereby renewed in a contemporary and digital way. (Launay 2006).

The analyses also show that an androcentric conception of the musical world runs through these digital music mediation devices. The system of representation that accompanies the staging of the characters conveys norms, values, as well as sound and visual representations, that assign distinct roles and functions to men and women in the musical milieu.

If, as we are reminded by Sylvie Octobre and Frédérique Patureau, “the institutions of the world of art and culture play a leading role in shaping the imagination of everyday life and the place of women in the world” (Octobre and Patureau 2018, 7-25), we might ask what the effects are of the gendered representations conveyed to users by these devices. This concept of “devices” provides an opportunity to adopt an intermediate scale, which not only helps us study the way in which these gender relations are established in digital, sound, visual, and lexical equipment, but also encourages us to consider what they in turn are shaping (Bonnéry 2009). Do these gender-stereotyped digital devices for mediating music influence gendered variations in instrument learning, women’s musical vocations, and cultural participation? Indeed, because they have both a normative and prescriptive effect on their audiences through the discourses and representations they convey, devices (whether digital or not) participate in musical socialization (Ravet 2007; Monnot 2012) and can, for example, contribute to reproducing gender norms and stereotypes. In a context where public and private bodies are taking greater account of gender inequalities and discrimination, we hope that the results of this work will help cultural institutions reflect on the production of digital content for the mediation of music.

This article was initially published in French, in the journal Digital studies. Kirchberg, I. 2022. “Une médiation de la musique au masculin? Analyse des dispositifs numériques de médiation de la musique produits par les institutions musicales.” Digital Studies / Le champ numérique 12. DOI: 10.16995/dscn.8100.↩︎

www.facebook.com/icimusique/videos/1689343171105164/ (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

sites.arte.tv/360/fr/giuseppe-verdi-messa-da-requiem-360deg-360 (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

www.orchestredeparis.com/figuresdenotes/index.php?page=game (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

mediationdelamusique.oicrm.org/result/aida-balado/ (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

digital.philharmoniedeparis.fr/CMDA/CMDA100000100/default.htm (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

www.mcc.gouv.qc.ca/index.php?id=6294 (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

The concept of horizontal segregation refers to the fact that women and men do not tend to hold the same kinds of jobs. For example, the field of teaching and music pedagogy is heavily feminized. Vertical segregation refers to the fact that men and women have unequal access to jobs with high levels of power and prestige.↩︎

The expression “Men Set the Tone” mentioned in the title refers to the title of an episode of the podcast Les couilles sur la table (literally, ‘balls on the table’, but closer to the meaning of ‘man up’) produced by Binge Audio and whose full title is “En musique, les hommes donnent le la” (Tuaillon 2019).↩︎

In 8 out of 10 cases, the voiceovers narrating the devices or explaining how they work are those of men.↩︎

For a more in-depth look at “voice issues” in relation to gender, see Prévost-Thomas and Ravet (2007).↩︎

Applying an intersectional perspective to this corpus would also be revealing. In the case of this specific application, for example, Moneim Adwan is the only non-European composer listed.↩︎

www.youtube.com/watch?v=EOOuqdn7MTE (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

mediationdelamusique.oicrm.org/recherche_motcle/?csrfmiddlewaretoken=JUKqNSAB9C8X5iE8uLa64F7VSCfBFwIGeMQXb1gJYXXdCKYnop7dLLBH67CH9HfT&q=log-book (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

mediationdelamusique.oicrm.org/recherche_motcle/?csrfmiddlewaretoken=6LrEN0Nyhcb6enYzeOSMKNvROKidUaUfBDxbb9tG6x0mLPiO8sPTrTZD2fFjolrs&q=dina (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

www.insulaorchestra.fr/c/guide-du-spectateur (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

ibid.↩︎

ibid.↩︎

pad.philharmoniedeparis.fr/doc/CIMU/1044658 (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

pad.philharmoniedeparis.fr/CMDA/CMDA100000100/default.htm, pad.philharmoniedeparis.fr/CMDA/CMDA100001900/default.htm

and pad.philharmoniedeparis.fr/CMDA/

CMDA100000500/default.htm (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

www.youtube.com/watch?v=VjZTeW2f3LM, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ownOhz-e4W8 and www.youtube.com/watch?v=547JgGIDiZM (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

youtu.be/LtnTtZ3eepI (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

digital.philharmoniedeparis.fr/CMDA/CMDA000004900/default.htm (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

opera-maker.de/en/ (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

Some of the elements in this section were also noted by Margot Dubois-Lafaye in a poster entitled “Les représentations des femmes au sein des dispositifs numériques de la médiation de la musique” presented in the Music Mediation Seminar held in 2019-2020 at the Université de Montréal.↩︎

www.youtube.com/watch?v=2jzBFraa2fw and youtu.be/mwT1x_2S2YA (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

www.youtube.com/watch?v=7bZsfJ9dJXo (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

fr.calameo.com/read/003611669735db75fa52b?authid=mMd1YLsQZf31 (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

The first page of the online comic strip features a woman conductor. On page 4, the reader is invited to take stock of the obstacles that have hindered and continue to hinder women’s access to positions as conductors and composers.↩︎

fr.calameo.com/read/003611669735db75fa52b?authid=mMd1YLsQZf31 (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

mediationdelamusique.oicrm.org/result/don-giovanni-vu-par-ici-artv/ (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

youtu.be/AM-bUlabthM (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

www.insulaorchestra.fr/c/guide-du-spectateur (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

mediationdelamusique.oicrm.org/result/opera-play/ (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

mediationdelamusique.oicrm.org/recherche_motcle/?csrfmiddlewaretoken=3imSLcUEQGWUuBzs9BHG8TjJu6K6s7Iiyasp9lAMF1La13TH3fENPZNvIB7cWifv&q=les+%C3%A9l%C3%A9ments+invisibles (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

mediationdelamusique.oicrm.org/result/why-the-trombone-is-the-greatest-instrument/ (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

mediationdelamusique.oicrm.org/result/opera-play/ (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

www.insulaorchestra.fr/c/guide-du-spectateur (accessed July 22, 2024).↩︎

Beauchemin, William-Jacomo, Noémie Maignien, and Nadia Dugay. 2020. Portraits d’institutions culturelles montréalaises. Quels modes d’action pour l’accessibilité. l’inclusion et l’équité? Laval, QC: Presses de l’Université de Laval. Accessed July 22, 2024. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1h0p43q.

Beudon, Nicolas. 2014. “Les enjeux de la médiation numérique dans les institutions culturelles: 4e Rencontre “Médiation et numérique dans les équipements culturels” / 4e Semaine digitale – Bordeaux. Octobre 2014.” Bulletin des bibliothèques de France (BBF), no. 3. Accessed July 22, 2024. bbf.enssib.fr/tour-d-horizon/les-enjeux-de-la-mediation-numerique-dans-les-institutions-culturelles_64898.

Bonnéry, Stéphane. 2009. “Scénarisation des dispositifs pédagogiques et inégalités d’apprentissage”. Revue française de pédagogie, no. 167 (April-June): 13-23. DOI: 10.4000/rfp.1246.

Bousquet, Danielle, Stéphane Frimat, Anne Grumet, Brigitte Arthur, and Claire Guiraud. 2018. “Inégalités entre les femmes et les hommes dans les arts et la culture. Acte II: après 10 ans de constats, le temps de l’action”. Rapport no. 2018-01-22-TRA-031. Haut Conseil à l’Égalité entre les femmes et les hommes. Accessed July 22, 2024. haut-conseil-egalite.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/hce_rapport_inegalites_dans_les_arts_et_la_culture_20180216_vlight.pdf.

Buscatto, Marie. 2007. Femmes du jazz: Musicalités, féminités, marginalités. Paris: CNRS Éditions.

———. 2016. “L’art sous l’angle du genre. Ou révéler la normativité des mondes de l’art”. In Art et société: Recherches récentes et regards croisés. Brésil/France, edited by Alain Quemin, and Glaucia Villas Bôas. Marseille: OpenEdition Press. DOI: 10.4000/books.oep.1438.

Carrel, Marion. 2017. “Injonction participative ou empowerment? Les enjeux de la participation”. Vie sociale 19, no. 3: 27-34. Accessed July 22, 2024. shs.cairn.info/revue-vie-sociale-2017-3-page-27?lang=fr

Casemajor, Nathalie, Marcelle Dubé, Jean-Marie Lafortune, and Ève Lamoureux, dirs. 2017. Expériences critiques de la médiation culturelle. Laval, QC: Presses de l’Université de Laval.

Clément, Catherine. 1979. L’Opéra ou la défaite des femmes. Paris: Grasset.

Chagnard, Samuel. 2018. “(Re) présentations d’instrumentiste-instrument: variations des stéréotypes de genre en orchestre symphonique”. In Normes de genre dans les institutions culturelles, edited by Sylvie Octobre, and Frédérique Patureau, 101-162. Paris: Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication et Presses de Sciences Po. Accessed July 22, 2024. hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01924368.

CQM (Conseil Québécois de la musique). 2017. Cohorte Leadership numérique. Accessed July 22, 2024. www.cqm.qc.ca/1238/Leaders_numerique.html.

———. 2019. Grand Rendez-vous de la musique. Accessed July 22, 2024. www.cqm.qc.ca/121/Grand_rendez-vous.html.

Coulangeon, Philippe, and Hyacinthe Ravet. 2003. “La division sexuelle du travail chez les musiciens français”. Sociologie du travail 45, no. 3: 361-84. DOI: 10.4000/sdt.31922.

Détrez, Christine, and Claire Piluso. 2014. “La culture scientifique, une culture au masculin?” In Questions de genre, questions de culture, edited by Sylvie Octobre, 27-51. Paris: Ministère de la Culture - DEPS. Accessed July 22, 2024. shs.cairn.info/questions-de-genre-questions-de-culture--9782111281561-page-27?site_lang=fr.

Donnat, Olivier. 2005. “La féminisation des pratiques culturelles”. In Femmes, genre et sociétés, edited by Margaret Maruani, 423-431. Paris: La Découverte. Accessed July 22, 2024. www.cairn.info/femmes-genre-et-societes--9782707144126-page-423.htm.

———. 2010. “Les pratiques culturelles à l’ère numérique”. L’Observatoire 37, no. 2: 18-24. Accessed July 22, 2024. shs.cairn.info/revue-l-observatoire-2010-2-page-18?lang=fr.

Dorin, Stéphane, ed. 2018. Déchiffrer les publics de la musique classique. Perspectives comparatives historique et sociologique / Unravelling Classical Music Audiences: Historical, Sociological and Comparative Perspectives. Paris: Edition des archives contemporaines.

Foucault, Michel. 1972. “Théories et institutions pénales”. Dans Annuaire du Collège de France. 72e année. Histoire des systèmes de pensée. année 1971-1972, 283-286. Accessed July 22, 2024. 1libertaire.free.fr/MFoucault458.html.

Giron-Panel, Caroline, Sylvie Granger, Raphaëlle Legrand, and Bertrand Porot, eds. 2015. Musiciennes en duo: Mères, filles, sœurs ou compagnes d’artistes. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Green, Anne-Marie. 2006. De la musique en sociologie. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Kirchberg, Irina. 2018. Panorama de la médiation de la musique au Québec: Définitions, acteurs et enjeux. Montréal: Partenariat sur les Publics de la Musique (P2M) et Conseil Québécois de la Musique (CQM). Accessed July 22, 2024. p2m.oicrm.org/portrait-pratiques-de-mediation-de-musique-quebec-definitions-configurations-professionnelles-enjeux.

———. 2020. “Où en est la médiation de la musique au Québec? Panorama des actions selon les membres du Conseil québécois de la musique”. Revue Internationale Animation, Territoires Et Pratiques Socioculturelles, no. 18: 29-48. Accessed July 22, 2024. edition.uqam.ca/atps/article/view/814.

Kirchberg, Irina, and Michel Duchesneau. 2020. “Le parti pris disciplinaire de la médiation de la musique. Orientations politiques, pratique, recherche et enseignement au Québec”. La médiation de la musique: enseignement, pratique, recherche 7, no. 2: 53-77. DOI: 10.7202/1072415ar.

Lacerte, Sylvie. 2007. La médiation de l’art contemporain. Trois-Rivières, QC: Editions d’art Le Sabord.

Launay, Florence. 2006. Les compositrices en France au XIXe siècle. Paris: Fayard.

Ledru, Caroline. 2019. “Quelle place pour les compositrices dans les conservatoires. Le matériel pédagogique et son impact à la lumière du genre”. In La musique a-t-elle un genre?, edited by Mélanie Traversier, and Alban Ramaut, 275-288. Paris: Editions de la Sorbonne.

Lussier, Martin. 2015. L’appropriation de la médiation culturelle dans la Vallée-du-Haut-Saint-Laurent: Caractéristiques, besoins et enjeux des artistes et des travailleurs culturels. Montréal: Culture pour tous, Autour de nous et Services aux collectivités de l’UQAM. Accessed July 22, 2024. sac.uqam.ca/upload/files/LUSSIER.Martin_Culture_pour_tous_Lappropriation_de_la_m%C3%A9diation_culturelle_dans_la_VHSL_juillet2015.pdf.

Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignement supérieur. 2017. “Politique de la réussite éducative. Le plaisir d’apprendre, la chance de réussir”. Gouvernement du Québec. Accessed July 22, 2024. www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/PSG/politiques_orientations/politique_reussite_educative_10juillet_F_1.pdf.

Monnot, Catherine. 2012. De la harpe au trombone: Apprentissage instrumental et construction du genre. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Octobre, Sylvie. 2005. “La fabrique sexuée des goûts culturels: Construire son identité de fille ou de garçon à travers les activités culturelles”. Développement culturel, no. 150 (décembre). Accessed July 22, 2024. www2.culture.gouv.fr/culture/editions/r-devc/dc150.pdf.

———, ed. 2014. Questions de genre, questions de culture. Paris: Ministère de la Culture - DEPS. Accessed July 22, 2024. shs.cairn.info/questions-de-genre-questions-de-culture--9782111281561?site_lang=fr.

Octobre, Sylvie, and Frédérique Patureau, eds. 2018. Normes de genre dans les institutions culturelles. Paris: Ministère de la Culture - DEPS. Accessed July 22, 2024. shs.cairn.info/normes-de-genre-dans-les-institutions-culturelles--9782724623307?lang=fr.

———. 2020. “Sociétés, espaces, temps”. Sexe et genre des mondes culturels. Lyon. ENS Éditions. DOI: 10.4000/books.enseditions.15207.

P²M (Partenariat sur les publics de la musique), and CQM (Conseil Québécois de la musique). 2019. Catalogue raisonné de dispositifs numériques de médiation de la musique. Accessed July 24, 2024. mediationdelamusique.oicrm.org.

Pébrier, Sylvie. 2020. “La formation à la médiation dans les établissements supérieurs de la musique”. SIE 2020 001. Direction générale de la création artistique. Service de l’inspection de la création artistique. Accessed July 25, 2024. catalogue.philharmoniedeparis.fr/AloesSynchro/stockage/Pebrier-Courant-rapport-formation-mediation-enseignement-superieur-musique.pdf.

Perez-Roux, Thérèse, and Frédérique Montandon, eds. 2014. Les médiations culturelles et artistiques. Quels processus d’intégration et de socialisation ? Paris: L’Harmattan.

Prévost-Thomas, Cécile, and Hyacinthe Ravet. 2007. “Musique et genre en sociologie. Actualité de la recherche”. Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire, no. 25: 185-208. Accessed July 22, 2024. www.jstor.org/stable/44406381.

Rasse, Paul. 2001. “La médiation, entre idéal théorique et application pratique”. Recherche en communication, no. 13: 61-75. DOI: 10.14428/rec.v13i13.47193.

Ravet, Hyacinthe. 2007. “Devenir clarinettiste. Carrières féminines en milieu masculin”. Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales 168, no. 3: 50-67. DOI: 10.3917/arss.168.0050.

———. 2011. Musiciennes. Enquête sur les femmes et la musique. Paris: Autrement.

———. 2015. L’orchestre au travail. Interactions, négociations, coopérations. Paris: Vrin.

———. 2016. “Cheffes d’orchestre, le temps des pionnières n’est pas révolu!” Travail, genre et sociétés 35, no. 1: 107-25. Accessed July 22, 2024. shs.cairn.info/revue-travail-genre-et-societes-2016-1-page-107?lang=fr.

SMCQ (Société de musique contemporaine du Québec). 2015. “La série hommage I. Baby do (John Réa, compositeur)”. Accessed July 22, 2024. www.youtube.com/watch?v=BHX-N1j2msc.

Tuaillon, Victoire. 2019. “En musique les hommes donnent le ‘la’”. Les couilles sur la table. Binge Audio. No. 51 (October 31). Accessed July 22, 2024. www.binge.audio/podcast/les-couilles-sur-la-table/en-musique-les-hommes-donnent-le-la/?uri=en-musique-les-hommes-donnent-le-la%2F.

Vouilloux, Bernard. 2008. “Du dispositif”. Dans Discours, image, dispositif. Penser la représentation, sous la direction de Philippe Ortel, 15-31. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Musicologist and sociologist Irina Kirchberg is a visiting professor at the University of Montreal where she co-directs the DESS in music mediation. She has published several collective works such as Faire l’art. Analyser les processus de création artistique (2014), Bourdieu et la musique (2019), edited the first scientific journal issue dedicated to music mediation (RMOICRM, 2020) and is co-editor of Volume 11 of the journal Transposition. Musique et sciences sociales devoted to “Musical socialisations”. She is a co-researcher in the Étude Partenariale sur la Médiation de la Musique (EPMM) and in the Observatoire des Médiations Culturelles (OMEC). Irina Kirchberg co-founded the NPO Médiatrices et Médiateurs de la Musique du Québec (MeMuQ).

ISSN 2943-6109 – Volume 1 (2024) – DOI: 10.71228/ijmm.2024.17

This paper is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Parts of an article may be published under a different license. If this is the case, these parts are clearly marked as such.