This article offers an empirically based description and analysis of the social situation of musicians living and working in Austria whose activities include engagement in cultural and art mediation. The quantitative-empirical data confirms existing findings on the portfolio careers of musicians today: the vast majority of the musicians surveyed are engaged in a mix of activities (sometimes close to, sometimes distant from their artistic practice) in their everyday life as “artrepreneurs”, as a way to make their living in a challenging, neoliberalised working environment. Not only the range of their professional activities along real-time, ideal-time and economic dimensions are addressed, but also forms of employment, educational background, average annual net income and stress levels in the music profession. These musicians are compared with another group of musicians from the same data sample who were not active in cultural and art mediation at the time of the survey. In their interrelation, the results show how the handling of a preferably broad mix of activities and skills is rewarded in the musical field in economic terms, although the social situation nevertheless remains fundamentally difficult and precarious for many of the respondents. Finally, the extent to which practices of cultural and art mediation may contribute to the emergence of a new, socially and civically engaged type of musician of the future is discussed.

Cet article propose une description et une analyse empiriques de la situation sociale des musicien·ne·s qui vivent et travaillent en Autriche et dont les activités comprennent un engagement dans les pratiques de médiation culturelle et artistique. Les données quantitatives et empiriques confirment les conclusions existantes sur les carrières des musicien·ne·s d'aujourd'hui : la grande majorité des musicien·ne·s interrogé·e·s sont engagé·e·s dans un mélange d'activités (parfois proches, parfois éloignées de leur pratique artistique) dans leur vie quotidienne en tant qu'« artrepreneurs », comme moyen de gagner leur vie dans un environnement de travail difficile et néolibéralisé. L'étude porte non seulement sur l'éventail de leurs activités professionnelles, leur emploi du temps idéal et les dimensions économiques de leur activité, mais aussi sur leurs formes d'emploi, leur niveau d'éducation, leur revenu net annuel moyen et les niveaux de stress dans la profession musicale. Ces musicien·ne·s sont comparé·e·s à un autre groupe de musicien·ne·s du même échantillon de données qui n'étaient pas actifs dans la médiation culturelle et artistique au moment de l'enquête. Dans leur interrelation, les résultats montrent comment la gestion d'un large éventail d'activités et de compétences est récompensée dans le domaine musical en termes économiques, bien que la situation sociale reste fondamentalement difficile et précaire pour de nombreuses personnes interrogées. Enfin, la mesure dans laquelle les pratiques de médiation culturelle et artistique peuvent contribuer à l'émergence d'un nouveau type de musicien·ne·s de l'avenir, engagé·evs socialement et civiquement, est discutée.

Der vorliegende Artikel bietet eine empirisch fundierte Beschreibung und Analyse der sozialen Lage von in Österreich lebenden und arbeitenden Musiker_innen, die unter anderem auch kunst- und kulturvermittelnd aktiv sind. Dabei untermauern die quantitativ-empirischen Daten bereits vorliegende Erkenntnisse zu sogenannten Portfolio-Karrieren von Musiker_innen heute: Die überwiegende Mehrheit der Befragten übt in ihrem Arbeitsalltag einen Mix an (zum Teil kunstnahen, zum Teil kunstfernen) Tätigkeiten aus, um als „artrepreneurs“ den eigenen Lebensunterhalt in einem herausfordernden, neoliberalisierten Arbeitsumfeld bestreiten zu können. Die Bandbreite ihrer beruflichen Tätigkeiten entlang zeitlich-realer, zeitlich-idealer und ökonomischer Dimensionen wird dabei ebenso beschrieben wie Formen der Beschäftigung, das Ausbildungsniveau, das durchschnittliche Jahresnettoeinkommen sowie Belastungen im Berufsalltag dargelegt werden. Die Ergebnisse werden außerdem mit einer Gruppe von Musiker_innen aus dem gleichen Datensample verglichen, die zum Befragungszeitpunkt nicht kunst- und kulturermittelnd tätig war. In ihrem Zusammenspiel zeigen die Daten auf, dass die Bewältigung einer möglichst breiten Kombination an unterschiedlichen beruflichen Tätigkeiten im Musikfeld in ökonomischer Hinsicht belohnt wird, wobei aber dennoch die soziale Lage vieler Befragter in beiden Vergleichsgruppen grundsätzlich prekär und schwierig bleibt. Abschließend wird diskutiert, inwiefern Praktiken der Kunst- und Kulturvermittlung womöglich zur Herausbildung eines neuen, sozial und zivilgesellschaftlich engagierten Musiker_innen-Typs beitragen.

Musicians as mediators, social situation, portfolio careers, neoliberalism, socially engaged art

With regard to the skills that will be relevant for (classical) musicians in the 21st century, conductor Sir Simon Rattle predicted over twenty years ago: “To be a performing artist in the next century, you have to be an educator too” (Rattle cited in Gutzeit 2014, 21). In the course of an interview given on the music mediation project Rhythm Is It!1 back in 2003, Rattle made the changing demands on classically trained musicians in a rapidly transforming society even clearer:

We have been educating people for many years to be a certain type of person. We have been educating for a society that maybe has gone. We need more and more creative people in society. We need more and more people who will make things connect together, who will glance at strange directions. We don’t only need good workers. These days are over. (Rattle 2004, n.p.)

The accuracy of his assessment may be seen today, twenty years later, not least in the current boom of music mediation, whose main aim is the creation of “multifaceted relationships between music and people” (Petri-Preis and Voit 2023, 25). In recent years, the field of music mediation has developed from a “purely field of practice”2 (Voit and Wimmer 2023, 13) with limited reach into a highly significant, increasingly independent, professionalised and institutionalised, steadily powerful player in current music and cultural life. By planning, realising and performing music in ways that are different to the usual ones, in collective processes involving different social “dialogue groups” (Schippling and Voit 2023), the practitioners of music mediation fulfil many of the demands formulated by Rattle: they strive for social connectedness via music, for which they have to think outside of the box and guide processes and projects creatively – and thus also make an important contribution to society. As a heterogeneous and extensive field of artistic-educational practice, music mediation has become an attractive (additional) option for many professionals in the musical field. In addition to a growing, but still small number of specialised full-time jobs at Austrian music institutions (Chaker and Petri-Preis 2022, 18), music mediation is often carried out as part-time work in the context of so-called portfolio careers3 (Wimmer 2021) and offers (additional) income opportunities for musicians.

Music mediation is currently run by “actors with heterogeneous formal (academic) qualifications and different professional backgrounds” (Chaker and Petri-Preis 2022, 11; Petri- Preis 2023, 95-99). In the course of increasing professionalisation and specialisation of music mediation practices in recent years (Chaker and Petri-Preis 2019), the number of specialised training and further education programs in this field is steadily growing4. As a result, however, the mastery of music mediation is increasingly becoming a kind of “fait social”, in the sense of Emile Durkheim, for music professionals, i.e. a necessity which can hardly be ignored and which “as a fixed mode of action […] has the capacity to exert an external constraint on the individual” (Durkheim 1984 [1895], 114). Music mediation skills are increasingly expected in the field of (classical) music today – they are thus changing from a former optional “add-on” to a “must-have” (Chaker and Petri-Preis 2023), a necessary ability if one wants to be successful in the current music labour market.

In addition to a growing number of people currently specialising in music mediation and working as music mediators either on a permanent basis or as freelancers for one or more music institutions (e. g. [professional] orchestras, concert halls, theatres, museums, music training institutions), music mediation continues to be an interesting field of activity for many other professionals in the field of music, art and culture, including “directors, curators, dramaturges, concert designers, composers, music teachers and instrument pedagogues” (Petri-Preis 2023, 96). However, music mediation has always been of particular relevance for (classically) trained musicians (see, among others, Bennett 2016; Smilde 2022), although the practice is currently “increasingly extending to musicians of other styles and genres” (Petri-Preis 2023, 97). Musicians who live in Austria and also work as music mediators are at the centre of this article, with the main focus being on an analysis of their social situation. On the basis of quantitative data, the range of their professional activities, both along real-time and ideal-time dimensions and the economic dimension, as well as their forms of employment and educational background, average annual net income and stress levels in the musical profession are described in more detail. This sample is compared with a group of musicians who were not previously active in cultural and art mediation. Before looking at the empirical data in more detail, the quantitative results are framed theoretically in the following section. In addition to a brief explanation of what is meant by “social situation”, the context in which musical labour unfolds comes into view. It is assumed that the capitalist-neoliberal structuring of the labour market in late modernity has had a huge impact on the ways that musicians organise their work, as well as on the social situation of this occupational group and its self-image.

The social situation of musicians and artists is determined by various interdependent factors. The economic situation, i.e. the income situation and income opportunities, are closely linked to the training received and the possibilities of work organisation, working conditions and the form of employment (self-employed, employed, mixed forms) in the professional field(s), which in turn have a significant influence on a person’s legal status. This includes the tax situation as well as social security matters (e.g. health insurance, pension schemes, unemployment insurance, occupational disability insurance). Further training opportunities, as well as public and private funding opportunities, also play a role in the respective social situation of an occupational group. The extent to which all these factors interact with mental health has recently become a relevant topic in the academic observation of the social situation of musicians and artists.

The fact that academic and cultural-political attention is today being paid to the social situation of occupational groups, often as a result of empirical studies, presupposes a change in the perception and a redefinition of the term “social situation”. From the mid-19th century onwards, increasingly open references to poverty, social problems and social issues were accompanied by a fundamental reassessment of the social situation of individuals as part of social collectives and groups: since then, as Eckart Pankoke has argued, the social situation no longer appears as “predetermined fate” (Pankoke 2010, 260) or “externally determined destiny” (ibid.), but has been discussed much more fundamentally as a “systemic question of societal organisational principles” (ibid.). This allows an existing social situation to be critically scrutinised within the context of resource allocation conflicts, categories of social inequality and socio-structural power relations. In the recent past, “distribution struggles […] have assumed dramatic proportions in view of the fiscal limits of the welfare state […]” (ibid., 263) – struggles which revolve around questions of access to and the organisation of work and labour, especially in the late modern societies of the global north: “Under the pressure of globalisation, the labour question is becoming a key problem of socio-political governance” (ibid., 264).

For the field of art and culture in general, and for the field of music in particular, “the labour question” and its effects have always presented themselves in a special way. Upheavals and restructuring in work contexts and in the social situation have affected the whole cultural field from the early modern period at the latest, when processes of rationalisation, specialisation and professionalisation commenced in the course of early capitalist economic activity and a music market based on the division of labour began to emerge (Smudits 2008, 243).5 The observation that, historically speaking, fundamental societal transformations have gone hand in hand with the invention and subsequent widespread implementation of new communication technologies (e.g. the invention of writing, later reprography, picture and sound recording, electronic sound transmission and microphoning, digitalisation), which fundamentally changed society and culture as a whole, marks the starting point for the “mediamorphoses” concept developed since the 1980s at the Vienna Department of Music Sociology (Blaukopf 1989; Smudits 2002). Also the ways in which music is produced, disseminated and appropriated, the ideal concepts associated with music in and the roles that musicians can and should play in society, the working environment in which musicians are active, the (working) tasks that musicians perform, the skills that become relevant under the respective framework conditions, as well as identities and self-images – in other words, what it means to be a “musician” at a certain historical moment – change fundamentally in the course of a mediamorphosis: “a new type of music maker emerges” (Gensch and Bruhn 2008, 3).

In the recent past, today’s type of musician has repeatedly been labelled – sometimes quite enthusiastically and affirmatively, sometimes more critically – as “artrepreneurs” (Smudits 2008; Engelmann et al., 2012; Harvie 2013; Paulus 2018; Schwetter 2018) or as “musicpreneurs” (Kubacki and Croft 2011; Paulus 2018; Rangadhithya and Ramanujam 2022), whereby such “frequent use of portmanteau words [...] can certainly be regarded as an indication of social changes” (Schwetter 2018, 185). In the course of the electronic and later digital mediamorphosis in modern capitalist societies,

a new type of musician has emerged, who, in terms of habitus, could be described as a music trader. Their aim is not to become a big act, a ‘star’, but to achieve a certain economic independence by diversifying their areas of work, which in the long term also enables them to do what they enjoy artistically. This more commercially sober than artistically idealistic relationship to one’s own work [...] could perhaps be [...] [described as] an artrepreneurial mode of production (Smudits 2008, 261).

This entrepreneurial turn, which has been observed among artists in general and in the musical field in particular over the past few decades (see also Haynes and Marshall 2017), is related to an increasing cultural-political thematisation and treatment of art and culture “as a real economic sector” (Menger 1999, 543). The encroaching neoliberalisation of the cultural labour market is also due to the fact that musicians nowadays have to manage and reconcile a wide variety of activities in the course of their profession, including many activities that are only remotely connected to art. The predominantly neoliberal influence on the “music labour market, with little employment on offer, means musicians do not generally engage in non-standard work from choice (Menger, 1999). […] [Musicians] might be called ‘accidental entrepreneurs’, since most of them did not set out to start a business. Their work mode is contingent on their choice of career” (Coulson 2012, 251).

The development of an entrepreneurial attitude occurs within the context of the demands placed on musicians today by a neoliberally structured labour market. According to David Harvey, the term neoliberalism describes “in the first instance a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterised by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade, consistently ignoring the huge impact of social inequality factors. The role of the state is to create and preserve an institutional framework appropriate to such practice” (Harvey 2005, 2; see also Giroux 2005), which in many countries is accompanied by an increasing “withdrawal of the state from many areas of social provision” (Harvey 2005, 3). However, the reach of neoliberalism extends far beyond purely economic concerns – it has caused “‘creative destruction’ not only of prior institutional frameworks and powers (even challenging traditional forms of state sovereignty) but also of divisions of labour, social relations, welfare provisions, technological mixes, ways of life and thought, reproductive activities, attachments to the land and habits of the heart” (ibid.). By emphasising the advantages of individual freedom of choice, i.e. shaping one’s own life in a self-determined way, and stressing the need to take responsibility for one’s own life, people are called upon to take “personal responsibility for making themselves employable in an insecure, competitive labour market” (Coulson 2012, 252, with reference to Banks and Hesmondhalgh 2009). Carina Altreiter (2023, 131) also states that “increasing demands for self-control in the labour process [by imposing] an active role on people in the transformation of labour capacities into labour efforts” (ibid.) points to a “new quality in the appropriation of labour” (ibid.), as well as to a “new quality of exploitation” (ibid.). Moreover, these practices of subjectivation are closely linked to the “flexibilisation and deregulation” (ibid.) of work processes, which in turn reinforce tendencies towards precarity and are accompanied by insecurity, unpredictability and existential fears for many people, although at the same time, they may have a (self-)disciplining effect (ibid.). As will be shown below, the field of music, like the cultural field as a whole, is affected by the neoliberalisation of labour, which also has an impact on the social situation of creatives today.

For Austria and Germany, in particular, it should be noted that the field of classical music, at least, was not and is not exposed to the free play of market forces in the same way as it is in many other countries – here, “the corrective music policy of the public sector became almost the only guarantor of the (survival) of traditional bourgeois music culture” (Smudits 2008, 245) in the 20th and 21st centuries. However, musical life in the German-speaking countries is also increasingly subject to neoliberal principles of thinking and structuring (e.g. the closure of publicly financed music venues, discontinuation of music events, reduction of permanent positions in orchestras and theatres, merging of orchestras etc.). This implies changes in the way musical labour is organised and in the social situation of musicians, as has already been the case in other countries of the global north for a longer period of time: “[F]ewer long-term employment jobs in the traditionally secure areas such as orchestras and full-time teaching are available […], short-time employment and freelancing are on the increase” (Polifonia 2007, 13, cited after Gee and Yeow 2021, 341). The “discontinuity of activity” (Benhamou 2003, 70), which is linked to the flexibilisation of work, has also found its way into the creative sector in German-speaking countries, i.e. “[i]ndividuals undertake several jobs at the same time; they also switch from one job to another, since projects are limited in time […]” (ibid). Musicians today are thus faced with the challenge of developing a “multiplexity of identities” (Gee and Yeow 2021, 341-342), although its composition may change over a lifespan (ibid., 346) and, on the side of requirements, is accompanied by the mastery of a “multiplexity of skills” (ibid., 342). Due to constantly changing requirements, musicians must constantly adapt their skills to new and different contexts in the course of “flexible specialisation” (Hesmondhalgh 1996). This is one reason why the career paths of musicians today are very different and difficult to compare: “[…] there is no ‘typical musician’, with most adopting a portfolio career, encompassing a multitude of roles including teaching, performing and writing” (Gee and Yeow 2021, 339). Rainer Prokop and Rosa Reitsamer recently observed something very similar for those classically trained musicians in Austria who are on the cusp of entering the labour market, with the researchers labelling the emergence of individualised career paths of musicians as “do-it-yourself (DIY) careers” (Prokop and Reitsamer 2023). In these careers, music mediation represents an additional activity and income opportunity for today’s (especially classically trained) musicians, one which is becoming increasingly attractive and important for them, as the following empirical data will show.

The fact that the current working conditions are very challenging for people in the creative sector today can be substantiated by two empirical-quantitative studies conducted in Austria on behalf of the Austrian Federal Chancellery – Section Arts and Culture. The first, with the title “Zur sozialen Lage der Künstler und Künstlerinnen in Österreich” [‘On the Social Situation of Artists in Austria’], in which 1,850 respondents took part, was carried out in 2008 (Schelepa et al. 2008). Ten years later, a follow-up study entitled “Soziale Lage der Kunstschaffenden und Kunst- und Kulturvermittler/innen in Österreich” [‘On the Social Situation of Artists and Art- and Cultural Mediators in Austria’], based on 1,757 participants, was conducted by employees of L&R Sozialforschung6 and the österreichische kulturdokumentation (Wetzel et al. 2018).

The conditions under which artists live and work in Austria, and whether and which changes in their situation can be empirically discovered over time, are at the centre of both studies. In essence, the results across all artistic fields confirm trends and developments in Austria that are also known for artists from other countries and societies under similar economic and social conditions: Both studies show precarious forms of employment, with high rates of self-employment and a declining number of permanent positions for artists and cultural professionals in Austria across all sectors (Wetzel et al. 2018, 3). Discontinuous, hybrid and unbounded forms of employment dominate, often in the form of projects and networks that cross artistic disciplines, whereby employment contracts are usually short-term and often cover a more or less manageable period of time; income is usually derived from multiple forms of employment, usually from a combination of self-employment and employment “which can be followed by a complex social insurance situation with often negative consequences for social security” (ibid., 115) and may also lead to challenges in terms of tax law. Due to the high rates for self-employers and freelancers, artists in Austria generally have insufficient social security and are at an above-average risk of poverty compared to the Austrian population (ibid., 11). With regard to the economic situation, both studies show that the artists questioned have a below-average net income and “an unchanged low standard of living in relation to the population as a whole” (ibid., 111). Their social situation, which can be described as difficult in many respects, also leads often to high levels of psychological stress for many artists in Austria. Since there is no medium and long-term planning security for them, no “permanent security of good working and living conditions” (ibid., 11), their insecurities and existential worries are a lifelong companion. Even (temporary) fame and success are not a “guarantee for a continuous work situation” (ibid.), i.e. even for established artists, the profession remains fraught with risks and uncertainties in the long term, with corresponding negative effects on mental health. “High levels of stress are most frequently experienced in the area of income, followed by questions of social security” (ibid., 111), especially in terms of retirement provision and security in the case of a lack of commissions.

The data presented in the following sections is based on a special analysis of the more recent study on the social situation of artists and art and cultural mediators in Austria, which I commissioned from Petra Wetzel of L&R Sozialforschung in 2019 on behalf of the Department of Music Sociology at the mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna (Wetzel 2019a). There, the social situation of those musicians living and working in Austria who engaged in cultural and art mediation as part of their portfolio careers at the time of the survey is compared to the situation of a group of musicians who did not practice art and cultural mediation at that time. Although the practice of music mediation is increasingly being observed academically from different perspectives, there have only been a few qualitative or quantitative studies to date that provide empirically based information, e.g. on the origin, socio-demographic characteristics, educational backgrounds, acquired skills or working conditions of practitioners of music medation as an increasingly important segment of the music labour market (Wimmer 2010, EDUCULT and Netzwerk Junge Ohren 2020, and Petri-Preis 2022 are exceptions in this respect, and provide interesting opportunities for data comparison). Through the data presented in the following7, this article aims to contribute to reducing this gap in research on music mediation.

In addition to capturing artists’ self-description and self-definition of their artistic and creative activity, and collecting socio-demographic characteristics, particular attention is paid to the current employment and income situation, the utilisation of public funding, questions of social security and (academic) training, networking and mobility (Schelepa et al. 2008; Wetzel et al. 2018, 3). In the more recent survey, which was slightly adapted and expanded in terms of the questions asked, workload/stress factors and the assessment of subjective life quality were also surveyed (Wetzel et al. 2018). “Artists” are defined as those who “(also) create art professionally” (ibid., 4) and are active in the visual arts, performing arts, film, music or literature (ibid.). In addition to a respondent’s artistic activity, at least one of the following criteria had to be met for the data to be included in the analysis:

- Membership of an interest group, a professional organisation, an art association, a society for musical performing and mechanical reproduction rights

- Publication of at least one artistic work in the form of an exhibition, publication, production, etc. in the last five years

- Support from the Austrian Artists’ Social Insurance Fund or from other art- and culture-specific funding

- Completion of an artistic training programme

- Income from artistic activity (ibid., 5)

Since the total number of (at least partly) professionally active artists in Austria is unknown8, more than 200 Austrian art and cultural institutions and facilities (“organisations, interest groups, universities, art and cultural institutions, agencies” [ibid., 8]) were contacted in advance of the 2018 data collection. These institutions acted as multipliers in order to announce and disseminate the online questionnaire. The survey took place between the beginning of April and mid-May 2018 (ibid., 7), via self-selection sampling (cf. Döring/Bortz 2016), ultimately enabling the data from 1,757 respondents from various artistic fields and backgrounds to be used for the analysis.9

The total of 1,757 people questioned10 included 400 musicians11. The group of musicians was divided into two samples for special analysis of whether or not they were also engaged in cultural and art mediating activities at the time of the survey. Just under half of the musicians surveyed (46%, 185 people) answered in the affirmative to the question of whether they also did cultural and art mediation activities professionally. This group will be referred to in the presentation of results below by the abbreviation MU-CAMs. The other 215 musicians surveyed in 2018 (54%) stated that they did not practise any cultural and art mediation activities at the time of the survey – the results of this group are presented below under the abbreviation MU-NOs. The special analysis thus allows a comparison of the two groups of musicians formed along the variable cultural and art mediation activities being carried out or not, which are to be analysed in more detail with regard to the following aspects: the respective range of activities that the musicians surveyed engage in, their respective training and employment situation, their income, their social situation, as well as professional stress factors and the respondents’ perceived quality of life.

In order to gain an overview of the professional activities of artists in Austria, various categories were developed for the quantitative questionnaire based on theoretical findings and previous expert interviews (Schelepa et al. 2008, 49). The survey from 2008 distinguishes between “artistic work”, “art-related activities” and “activities distant to art”. In the follow-up study, from 2018, “cultural and art mediation” was included in the survey as a separate category for the first time. All activities aiming at the production and dissemination of “high-quality and professional art” fall under “artistic work” (ibid., 9). The category “activities distant to art” includes all “other professional activities that are not in the context of art [...], from academic work to craft professions to activities in the catering industry” (ibid., 50). In the 2008 study, “art-related activities” were defined as all tasks “that do not directly involve artistic creation per se, but which are very closely linked to the field of art” (ibid., 49). Examples cited include teaching in one’s own artistic field, as well as the exercise of organisational and/or journalistic tasks or cultural management tasks (ibid.).

The category of “art-related activities” was then split up for the more recent study: “art-related activities” now primarily include organisational and entrepreneurial aspects, while “art management, art therapy, etc.” are cited as examples of this (Wetzel et al. 2018, 37). The “educational and/or communicative mediation of art and culture (e.g. through guided tours, projects, lectures, teaching activities)” (Wetzel 2019b; cf. also Wetzel et al. 2018, 37) is understood as specifically “cultural and art mediating activities”, with the respondents also being able (but not obliged) to specify their cultural and art mediating work in an open category. There is therefore a certain lack of clarity regarding the exact delimitation of the activities that fall under the category of “cultural and art mediation”, since it is not possible to replicate in retrospect exactly whether the musicians surveyed, who may also give music lessons, either privately or at an institution such as a music school, categorised this activity as an “art-related activity” or as a “cultural and art mediating activity”12.

The mix of work activities can be seen for the 400 musicians surveyed: As Table 1 shows, only a good quarter (26%) of the musicians surveyed pursued exclusively artistic work in their professional lives. Three quarters of the participants combined different income opportunities, with the mix of artistic work in combination with mediating activities (22%) and the combination of artistic work, mediating activities and art-related activities (15%) being comparatively common in practice. The empirical data thus emphasises the need for three quarters of the musicians surveyed who work in Austria to support themselves by performing various activities and tasks beyond artistic work, thus confirming existing theoretical and empirical findings on hybrid employment relationships and portfolio careers in the field of music. For the clear majority of musicians questioned, artistic work is an important, but nevertheless only one component of their professional activity and the everyday business in which they pursue different activities. The data thus also shows a shift or transition in the core activities of today’s musicians. The majority of the musicians surveyed have a broad professional base and as “artrepreneurs” (see above) engage in a mix of different activities beyond their artistic practice in order to secure their livelihood in a challenging environment characterised by neoliberal considerations. In any case, many musicians appear to have discovered the field of cultural and art mediation as an additional field of activity and income for themselves – almost half (46%) of the respondents already integrated corresponding activities into their own portfolio back in 2018.

| Range of activities of musicians questioned | in percent |

|---|---|

| Exclusively artistic work | 26 |

| Artistic work + cultural and art mediation | 22 |

| Artistic work + cultural and art mediation + art-related activities | 15 |

| Artistic work + art-related activities | 12 |

| Artistic work + activities distant to art | 9 |

| Artistic work + art-related activities + activities distant to art | 7 |

| Artistic work + cultural and art mediation + activities distant to art | 6 |

| Artistic work + cultural and art mediation + art-related activities + activities distant to art | 3 |

Source: L&R Datafile ‘Soziale Lage Kunstschaffende, -vermittler/innen‘ (Wetzel et al. 2018), special evaluation of the musicians surveyed by Petra Wetzel on behalf of the Department of Music Sociology (mdw) in 2019, tabular preparation of the data by the author.

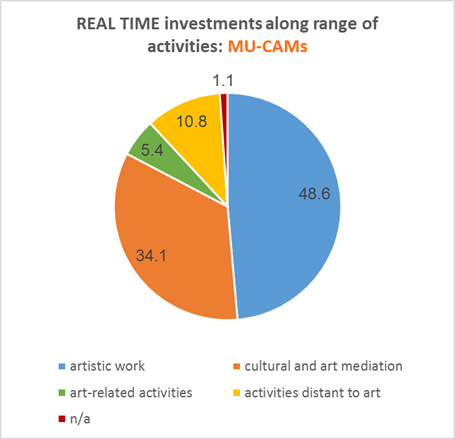

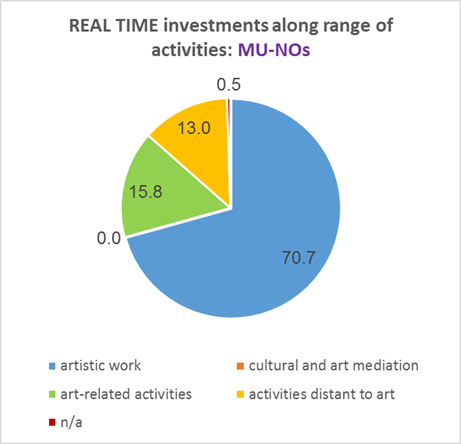

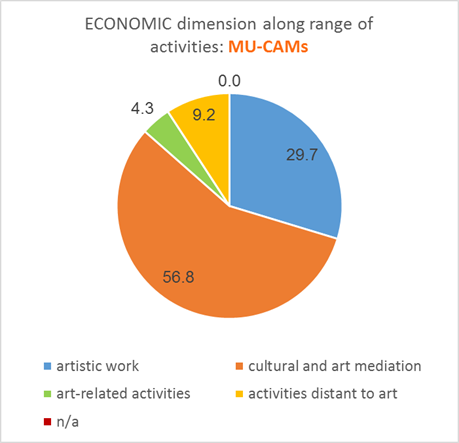

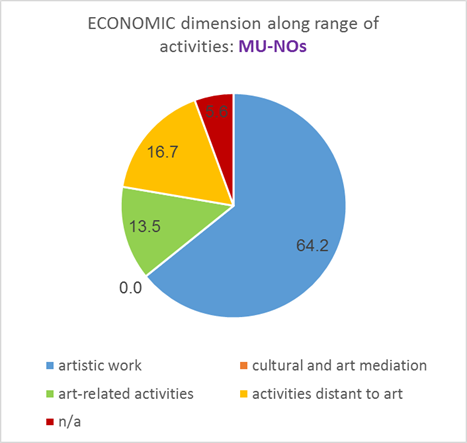

The following figures 1 to 6 show how much time the musicians surveyed actually invest on average in the different forms of activities described in the section before, which of them they pursue as part of their profession (real time investments), how much time they would ideally like to devote to the individual activities (ideal time dimension), and finally, which activities contribute to their income and to what extent (economic dimension). The 46% of musicians surveyed who engage in art and cultural mediation (MU-CAMs) are compared with the 54% who did not do so at the time of the survey (MU-NOs).

As Figure 1 shows, the MU-CAMs surveyed spend on average a good third of their available working time on culture and art mediation (34.1%). In direct comparison with the group of MU-NOs (see Fig. 2), they spend significantly less time on decidedly artistic work. Nevertheless, artistic work still accounts for just under half and thus the largest proportion of the working time (48.6%) of MU-CAMs, whereas MU-NOs spend the largest proportion of their working time, more than two thirds (70.7%), on artistic work. With regard to art-related activities, the proportion of time invested by MU-NOs is manageable at 15.8%, but three times as high as among MU-CAMs, who spend only 5.4% of their time on art-related activities. The proportion of time spent on activities distant to art, however, is almost the same in the comparison groups: at 10.8% (MU-CAMs) and 13.0% (MU-NOs).13

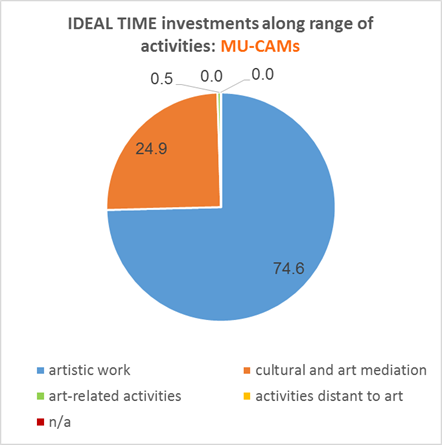

When asked how they would organise their time if they were free to choose, the MU-CAMs (see Fig. 3) responded that they would like to spend three quarters of their working time (74.6%) on artistic work. The remaining working time – around a quarter of the time available (24.9%) – is time which the MU-CAMs would like to devote to cultural and art mediation. This is relevant insofar as the result shows that musicians who engage in cultural and art mediation would not want to abstain from this activity and the resulting learning experiences, but would at best reduce the time spent on mediating activities in favour of artistic work (from the actual 34% to 25% of the work quota). Art-related and non-art-related activities would have no place for them in an ideal, desired work setting.

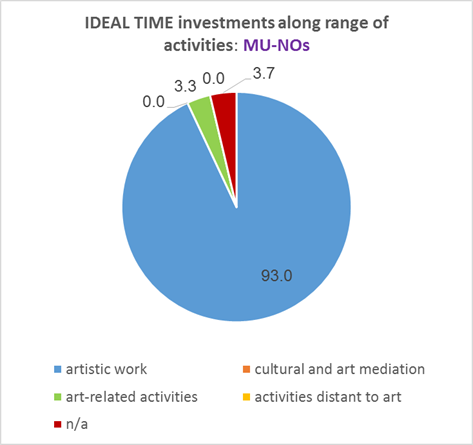

In the comparison group, those musicians who were not involved in cultural and art mediation at the time of the survey (see Fig. 4) would dedicate almost all of their working time to artistic work (93.0%). Ideally, MU-NOs would devote 3.3% of their working time to art-related activities, while they would gladly forego non-artistic activities completely. The MU-NOs left open how they would invest a further 3.7% of their time.

The presentation of the economic dimension, i.e. which activities currently generate which share of the total individual income in economic terms, can help explain why musicians who are already active in art and cultural mediation can neither do without this field of activity nor do they want to (see Fig. 5): According to their own statements, MU-CAMs generate the majority of their income (57%) through art and culture mediating activities. Almost a further third of their income (29.7%) results from their artistic activities, while a further 9% and 4% of MU-CAMs’ income comes from non-art and art-related activities respectively.

By contrast, musicians who were not active in cultural and art mediation at the time of the survey generated almost two thirds of their income from their artistic work (64.2%, see Fig. 6). A further 16.7% of their income came from activities distant to art, and 13.5% of the income in the group of MU-NOs was generated from activities related to art. 5.6% of income could not be allocated to the predefined categories.

The presentation of the economic dimension at this point does not yet say anything about the amount of income achieved in the two comparison groups, which will be considered in more detail below.

Regardless of whether the musicians surveyed were active in the field of cultural and art mediation at the time of the survey or not, three quarters of the study participants stated that they combine self-employed and employed activities in their day-to-day professional practice (MU-CAMs: 73.7% [N=167], MU-NOs: 72.9% [N=85]). A further quarter in both survey groups claimed that they are exclusively self-employed (MU-CAMs: 25.1%, MU-NOs: 25.9%). Only 1.2% of respondents in both groups said that they were exclusively employed.

However, as a detailed analysis shows, the form of employment differs depending on the type of activity carried out (artistic work, cultural and art mediation, art-related activities, activities distant to art, see above). Only the form of employment in the context of cultural and art mediation will be discussed in more detail here: when engaged in cultural and art mediation, 40.8% of the MU-CAMs (N=179) do this work exclusively self-employed, 34.1% are exclusively employed, and 25.1% do mediation work in a mixed form of self-employment and employment. Although musicians’ cultural and art mediation activities are often, or even predominantly, carried out as self-employed work, the field also offers the possibility of employment (and thus access to social security benefits) to an above-average extent, which is otherwise rarely the case in the field of music (see above).

As the 2018 study on the social situation of artists in Austria shows, musicians are comparatively well off in terms of their total net income, compared to their colleagues in other fields of the arts (Wetzel et al. 2018, 69-81). In the field of the visual/fine arts for example, the arithmetic mean was €13,802 net in 2017, and the median value14 in this group was €11,000 net (N=453, ibid., 198). The musicians surveyed, on the other hand, achieved the highest arithmetic mean income value of all artist groups with a personal annual income of €23,998 net in 2017. However, the median in the group of musicians was only €16,456 net (N=366) and thus, as far as the field of the arts is concerned, only somewhat above the average15, which indicates a wide spread of income levels in the music sector.

Compared to data on the income situation of the Austrian population as a whole, the quality of life of artists in Austria – and this also applies, albeit to a lesser extent, to large parts of the group of musicians surveyed – must, in economic terms, be described as precarious and below average (ibid., 71-73, 115): “For a good proportion of artists, against this background, it is in fact not a question of monetary profit-making, but rather of economic survival, the continuability of regular artistic activity and securing their livelihood” (ibid., 115).

In the course of the special analysis, the question as to whether any differences within the group of musicians surveyed with respect to the variable “cultural and art mediation – done or not” was investigated in terms of the average annual personal net income.

MU-CAMs (N=172) |

MU-NOs (N=194) |

Musicians (total) (N=366) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Personal annual income (net): Arithmetic mean |

€29,640 | €18,995 | €23,998 |

Personal annual income (net) Median |

€17,685 | €14,515 | €16,456 |

Source: L&R Datafile ‘Soziale Lage Kunstschaffende, -vermittler/innen’ (Wetzel et al. 2018), special evaluation of the musicians surveyed by Petra Wetzel on behalf of the Department of Music Sociology (mdw) in 2019, tabular preparation of the data by the author.

As Table 2 shows, the MU-CAMs (N=172) earned an average net income of €29,640 in 2017, if the arithmetic mean is considered, when all fields of income are taken into account. No other group in the study by Wetzel et al. achieved a similarly high net income if the arithmetic mean is applied (cf. Wetzel et al. 2018, 198). The net income in the group of the MU-NOs (N=194), i.e. €18,995 net, was more than €10,000 lower in 2017.

If the median value is considered, differences between the two comparison groups are still present, but less sharp: half of the MU-CAMs earned up to €17,685 net in 2017, while the median value for the group of MU-NOs was €14,515.

The significantly higher amount of income in the group of MU-CAMs is related to the fact that MU-CAMs more often work full-time than the questioned MU-NOs. While 80.6% of MU-CAMs (N=165) reported working full-time and just under one in five (19.4%) work part-time up to 36 hours a week, only two thirds (67.8%) of the MU-NOs (N=171) work full-time, whith one third (32.2%) working part-time up to 36 hours a week.

The increasing importance of mediating skills in the field of music is evidenced by responses of the MU-CAMs surveyed to the question of how the proportion of their total income from activities in the field of cultural and art mediation has developed over the past ten years (N=170). 40.6% of the MU-CAMs stated that the proportion of their total income from cultural and art mediation has increased in recent years, while for 29% of them, the proportion has remained stable in recent years. 22% of the MU-CAMs stated that the share of income from activities in the field of cultural and art mediation of their total income has fluctuated over the past ten years, while for 8% it has decreased.

All in all, the data on the income situation of musicians living and working in Austria shows that a broad positioning in various fields of work, the mastering of different tasks and forms of employment, as well as professional flexibility, are all economically rewarded in today’s neoliberally structured (music) labour market setting.

Those musicians surveyed who are also active as cultural and art mediators have above-average qualifications in relation to the comparison group in terms of their artistic training background: 95.5% of the MU-CAMs (N=177) have received specific artistic training (for example at public or private music schools, in private lessons, at music academies, conservatories or universities), compared to 85.2% of the respondents in the group of MU-NOs (N=210).

Furthermore, it was asked whether the musicians had completed an academic artistic training. 78.0% of the MU-CAMs (N=185) had completed an academic artistic training (while 22.0% of the respondents in this group had not done so). The picture is different in the group of MO-Nos: Just over the half of the MU-NOs (51.0%, N=215) had an academic degree, whereas the other half of respondents (29.0%) had not completed their academic education.16

More than half of the Austrian musicians surveyed, regardless of whether they are involved in cultural and art mediation or not, experience a de-limitation of work (MU-CAMs: 52.2%, N=184, MU-NOs: 51.6%, N=213), i.e. work and private life merge into one another: “[…] the professional and private spheres [...] become blurred” (Wetzel et al. 2018, 66). Moreover, the data shows that many of the respondents try to achieve a balance between their private and professional lives, i.e. try to blend both spheres: 42.4% of the MU-CAMs seek for an integration of professional and private life, while a good third of musicians in the MU-NO- group (37.1%) tries to do so as well. Only 11.3% of the respondents in the MU-NO-group and 5.4% of MU-CAMs strive for segmenting their professional and private lives strictly. Altogether, the data shows that for the vast majority of the musicians surveyed, the professional and private spheres are closely interconnected.

In the study on the social situation of artists in Austria, the respondents were also asked how stressful they perceive their profession to be overall and how different stress factors present themselves in detail. With regard to the overall stress experienced, the special analysis of the musicians questioned reveal little or no significant differences between the two comparison groups: around half of the respondents feel a medium level of stress (50.8% of the MU-CAMs [N=120] and 46.5% of MU-NOs [N=140]). In each case, just over a quarter of the musicians surveyed – MU-CAMs: 26.7%, MU-NOs: 25.0% – speak of an overall perceived low level of stress. In contrast, 28.5% of the MU-CAMs and 22.5% of the MU-NOs feel a high level of stress.

With regard to individual stress indices, however, there are differences between the two comparison groups. The respondents were asked to assess the perceived stress with regard to selected items along a four-point Likert scale (1=not stressful, 2=less stressful, 3= rather stressful, 4=very stressful), i.e.: “The higher the mean value, the more stressful the aspect is perceived” (Wetzel et al. 2018, 48).

| Stress levels | Group | Arithmetic mean |

N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creativity/productivity: Administrative/organisational work is at the expense of creative/productive work | MU-CAMs | 3,03 | 150 |

| MU-NOs | 2,74 | 191 | |

| Employment situation (overall) | MU-CAMs | 2,33 | 141 |

| MU-NOs | 2,20 | 165 | |

| Detail: Multiple employment | MU-CAMs | 2,42 | 144 |

| MU-NOs | 2,39 | 172 | |

| Detail: Irregular working time | MU-CAMs | 2,19 | 154 |

| MU-NOs | 2,08 | 183 | |

| Social security (overall) | MU-CAMs | 2,85 | 148 |

| MU-NOs | 2,90 | 181 | |

| Detail: Ensuring social security in the event of illness, accident | MU-CAMs | 2,77 | 158 |

| MU-NOs | 2,94 | 192 | |

| Detail: Ensuring social security for old age | MU-CAMs | 3,06 | 162 |

| MU-NOs | 3,18 | 196 | |

| Detail: Ensuring social security in the event of unemployment | MU-CAMs | 2,84 | 155 |

| MU-NOs | 3,14 | 193 | |

| Income (overall) | MU-CAMs | 2,69 | 141 |

| MU-NOs | 3,03 | 170 | |

| Detail: Income uncertainty, regularity of income | MU-CAMs | 2,70 | 159 |

| MU-NOs | 3,09 | 194 | |

| Detail: independent income to secure own livelihood | MU-CAMs | 2,63 | 150 |

| MU-NOs | 3,11 | 184 | |

| Detail: unpaid labour/performance of work without pay | MU-CAMs | 2,74 | 150 |

| MU-NOs | 2,85 | 185 |

Source: L&R Datafile ‘Soziale Lage Kunstschaffende, -vermittler/innen’ (Wetzel et al. 2018), special evaluation of the musicians surveyed by Petra Wetzel on behalf of the Department of Music Sociology (mdw) in 2019, tabular preparation of the data by the author.

As can be seen in Table 3, the MU-CAMs rate their work and employment situation as somewhat more difficult than the MU-NOs do. The fact that administrative and organisational tasks come at the expense of creative activities is a particular problem in this group, not least due to the fact that a particularly large number of thematically different activities have to be reconciled in this group. The irregular working time outside of a 9-to-5 schedule is rated as “less stressful” on average in both comparison groups and does not appear to be a primary problem for the musicians surveyed.

With regard to questions of social security, both overall and in detail, these are consistently described as more difficult by the MU-NOs than by the MU-CAMs, with questions of social security in old age, in particular, showing a rather high stress index in both groups. With regard to social security in terms of unemployment, MU-NOs also express higher concern, probably due to the fact that this group lacks activities in cultural and art mediation as an additional mainstay, which in some cases also opens up access to the Austrian social security system. In view of the income situation and questions of livelihood security, the stress factor in the group of MU-NOs is also higher than in the comparison group, which can be seen in connection with the clearly lower annual income (see above) earned by musicians who had not been involved in the field of cultural and art mediation at the time of the survey. Unpaid labour is performed in both survey groups, although the extent of this was generally rated as rather stressful by the respondents.

When asked about their overall subjective well-being, the results among the musicians surveyed in both groups are rather sobering: in the group of MU-CAMs (N=172), just under half of the respondents (47.1%) categorised their current subjective well-being status as “medium”, 42.4% of the participants described it as “low”, and just one in ten people (10.5%) described it as “high”. In the group of MU-NOs (N=208), the gap in terms of subjective well-being within the group is wider than in the comparison group: exactly half of the respondents (50.0%, and thus comparatively more musicians than in the MU-CAM-group) described their subjective well-being as “low” at the time of the survey. In contrast, however, slightly more respondents in the group of MU-NOs, namely 14.4% and thus every 7th person, stated that their subjective sense of well-being was “high”. Finally, a good third of the MU-NOs surveyed (35.6%) characterised their subjective sense of well-being as “medium”. In terms of quality of life and subjective well-being, the musicians questioned are thus clearly below the values determined for the population in Austria as a whole, regardless of whether they engage in cultural and art education or not: only a good fifth of the population in Austria speaks of a low level of subjective well-being, whereas a good quarter of the overall population perceives the quality of life as high and more than half of the population in Austria speaks of a medium level of subjective well-being (cf. Wetzel et al. 2018, 113).

Musicians who live and work in Austria and who are also active as cultural and art mediators in the course of their portfolio careers were the focus of this article, whereby their social situation, in particular, was analysed and compared with that of a group of musicians from the same data sample who were not active as mediators at the time of the survey. The quantitative-empirical data confirm recent findings on the portfolio careers of musicians: the vast majority of the musicians surveyed are engaged in a mix of activities (sometimes close to, sometimes distant from their artistic practice) in their everyday professional practice as ‘artrepreneurs’, in order to make their living in a challenging, neoliberal working environment. At the time of the survey, almost half of the respondents had already discovered the field of cultural and art mediation for themselves and integrated this artistic-educational practice into their own career portfolio. The data clearly shows that the activity of cultural and art mediation plays an important role for the musicians in question, not least as an additional source of income – more than half of the income in this group is generated through mediating activities. With regard to the average annual net income, the data for the musicians questioned shows as a whole a wide spread in income levels, with musicians who were also active as cultural and art mediators at the time of the survey having the highest net income of all artistic respondent groups included in the study by Wetzel et al., with an average total annual net income of €29,640 as an arithmetic mean for 2017 (cf. Wetzel et al. 2018, 198). Musicians who refrain from mediation activities earned around €10,000 less on average in the same year. The data on the income situation of the musicians who participated in the study thus indicates that, within today’s neoliberally structured (music) labour market, the performance of various tasks and, in particular, the performance of a still rather new, innovative practice such as music mediation in the sense of flexible specialisation is economically rewarding. However, with regard to their current work and employment situation, those musicians who are practising music mediation also describe it as more challenging and stressful than the comparison group. The fact that administrative and organisational tasks, in particular, come at the expense of creative activities was perceived as more of a problem in this group than among the musicians who do no cultural and art mediation – probably because the former group has to juggle a considerably larger number of different activities. On the other hand, musicians who are not involved in mediation consistently described issues of securing their livelihood and social security as more difficult. Especially with regard to social security in the event of a lack of projects/orders, musicians in this group described themselves as more stressed, which can certainly be seen in connection with the fact that they lack the mainstay of cultural and mediation as an additional income opportunity, which sometimes also opens up access to the Austrian social security system. With regard to the question of social security in old age, however, the stress index is similarly high in both groups. In terms of quality of life and subjective well-being, the musicians surveyed, regardless of whether or not they work as mediators, are significantly below the values assumed for the Austrian population as a whole. Although those musicians who are already doing cultural and art mediation are clearly better off in terms of income than their colleagues in the comparison group, their social situation remains nevertheless challenging and is also characterised by poor compatibility, planning uncertainties in the course of hybrid forms of employment, the risk of poverty and a lack of future prospects, so that the social situation of the musicians surveyed must be described as precarious overall.

To conclude, the fact that musicians who are already active as cultural and art mediators do not want to miss this activity, even if they could, is worthy of special consideration. Instead, they would gladly and voluntarily dedicate a quarter of their working time to mediating activities. In my opinion, this indicates a shift or a transition in the core activities of today’s musicians, which can possibly be interpreted in connection with a general societal reorganisation and reorientation. In view of the current multiple global crises, combined with the assumption that the whole world will change with the occurence and societal implementation of AI as a new communication technology, we are possibly on the threshold of a new mediamorphosis. As theoretically outlined above, the emergence of a new type of musician in the course of the expected technological and societal transformation seems likely. I assume – and this brings us full circle to Sir Simon Rattle’s prediction at the beginning of this article – that mediating skills will play a central role in the life of this new type of future musician. A development in this direction would not only be in the interest of society, but also in the interest of the musicians themselves and could (at least I hope so) go hand in hand with an improvement in their social situation. It is one of the particular paradoxes that musicians under neoliberal market conditions “must compete for scarce resources, whether it is their share of the audience, funding in the public sector or whatever it may be; and yet the nature of the music profession is essentially co-operative” (Coulson 2012, 252) – or, to bring it to the point: “[…] music business is a ‘buddy’ business” (Engelmann 2012, 40). This paradox is particularly relevant for music mediators and musicians involved in cultural and art mediation: on the one hand, they are constantly addressed as ‘bridge builders’ who, as part of their professional practice, should develop and maintain cooperative behaviour with different dialogue groups in society. On the other hand, however, under neoliberal training and working conditions, they are called upon, on a daily basis, like all other creatives, to rival each other, “to deploy entrepreneurial skills, motivated by competitive self-interest rather than co-operation” (Coulson 2012, 252). However, Susan Coulson was already able to demonstrate the sometimes idiosyncratic way in which musicians deal with entrepreneurial requirements in everyday life:

Insecurity was the norm and many of the participants could be regarded as just getting by financially, but the value of having music at the centre of their working lives mitigated some of the more negative aspects and strengthened their sense of community and identity as working musicians. It is the communal, co-operative nature of music work that helps illuminate musicians’ understandings of being entrepreneurial. (ibid., 257)

Recent study results by Rainer Prokop and Rosa Reitsamer also show that at least some of the young and white, classically trained musicians they studied are developing a kind of “DIY ethos” (Prokop and Reitsamer 2023, 122), thus cultivating “alternative cultural practices” (ibid.) “that disrupt the competitive logic of entrepreneurialism” (ibid.). The fact that music mediation helps to promote “artistic citizenship” as an attitude in the sense of David Elliott et al. (2016) was recently demonstrated by Axel Petri-Preis. Among the musicians he qualitatively examined there were also some who

emphasise the identity-building, community-building and transformative potential of music. The musicians combine their artistic practices with mediation practices in order to enter into participatory processes with other people. In addition, they reflect on their artistic practices with regard to social and cultural frameworks and also the hegemonic position of classical music in the so-called Western world. Their goal of being socially effective is thus based on an attitude of artistic citizenship and is therefore a fundamental part of their identity as musicians (Petri-Preis 2022, 130).

It would seem that music mediation is much more than just another piece in the portfolio puzzle of today’s musicians. Likewise, Victor Renza and colleagues observe a general shift towards “social entrepreneurship” among artists in general: “Artists are assuming new roles, not only as agents that unite the community to confront social issues that affect them, but also as inspirers, instigators, initiators, and participants of social entrepreneurship projects” (Renza et al. 2024, 55). Do these observed shifts in the orientations and practices of musicians and artists possibly indicate the transition to a new, post-neoliberal phase in the course of a socio-ecological society? Do the great successes of music mediation (and of community music as well) in recent years – the practices which are perhaps particularly predestined to promote a complicity of resistance, cooperation and solidarity, not only among musicians, but above all with its dialogue groups in civil society – point to a different future society? In my view, the prospects are good that a strongly socially-committed type of musician, who is also a music mediator, can and will contribute in productive ways to the socio-ecological transformation of society in the near future.

I would like to thank Petra Wetzel of L&R Sozialforschung for her cooperation in the course of the special evaluation, as well as the mdw and Tasos Zembylas, former head of the Department of Music Sociology, for authorising the funding for the same. I would also like to thank Sebastian Engler for critically reviewing and commenting on this article.

For the music mediation project “Rhythm Is It!”, 250 pupils from Berlin got to know Igor Stavinsky’s ballet “Le Sacre du Printemps”, rehearsing the dances over months under the guidance of a professional team of artists. In 2003, they performed the piece with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under chief conductor Sir Simon Rattle.The film of the same name was released in cinemas in 2004.↩︎

For this article, Peter Waugh has translated all the original German-language quotations into English.↩︎

As Ian Whitney, Jennifer Rowley and Dawn Bennett point out, “[t]he term portfolio career was first used in the 1980s and refers to a portfolio of concurrent roles and income streams which are combined to create part-time or full-time work. In many cases there are both proactive and reactive components to these careers such that portfolio workers might proactively combine multiple roles in order to create more fulfilling work and/or reactively combine roles because of insufficient work or enforced transition. In the music sector, portfolios often include non-music work” (Whitney et al. 2021, 54).↩︎

For an up-to-date overview of training opportunities in the field of music mediation in German-speaking countries, see forum-musikvermittlung.eu/informationen (Accessed May 29, 2024).↩︎

Smudits classifies the gradually developing separation of composition and interpretation in musical practice from the early modern period onwards and the associated emergence of music distributors (publishers, concert organisers) as the “basis of an organisation of musical life based on the division of labour” (Smudits 2008, 243).↩︎

The name of the extra-mural research institute L&R Sozialforschung [L&R Social Research] is derived from the first letters of the founders’ surnames: Ferdinand Lechner and Walter Reiter, see www.lrsocialresearch.at/team (Accessed September 25, 2024).↩︎

I presented the data in joint lectures with my colleagues Axel Petri-Preis and Matthias Gruber back in 2019 and 2020 (Chaker et al. 2019; Chaker and Petri-Preis 2020). Very brief references to the data resulting from our joint work can be found in two publications by Axel Petri-Preis (Petri-Preis 2022, 110-111; Petri-Preis 2023, 98).↩︎

In 2008, it was assumed that there were around 18,000 people working in the creative sector in Austria; the more recent study estimates their number to be between 20,000 and 30,000 persons (Wetzel et al. 2018, 6), with an additional number of up to 2,500 people working in the field of cultural and art mediation to be added to this figure (ibid.).↩︎

The data therefore originates from the time before the coronavirus pandemic, which was, of course, very challenging for people in the creative sector, especially in the field of music and performing arts, due to the loss of opportunities to perform at live concerts and restrictions on teaching activities. As there are currently no such similarly extensive quantitative-empirical data sets available for Austria as those provided by Schelepa et al. (2008) and Wetzel et al. (2018) that could be taken into account for a special analysis, the data set from 2018 was used, although it can be assumed that the pandemic has further exacerbated the social situation of artists in Austria. However, empirical evidence of this is still pending.↩︎

In 2018, the specialised group of cultural and art mediators was included in the study for the first time and mentioned separately in the title, which already points to the growing social importance of this professional group and practice. This group comprised 145 people who work exclusively as art and cultural mediators and are not themselves artistically active (Wetzel et al. 2018, 4). As it was no longer possible to retrospectively examine the specific focus of activity and work context of the art and cultural mediators surveyed and it therefore remained unclear whether the participants work in museums, theatres, festivals or in the music sector, this group was not considered for special evaluation.↩︎

Overall, the sample of musicians shows a male predominance: a good two thirds of respondents (N=266) described themselves as male, just under a third (N=128) as female, and three people described themselves as inter/diverse (the latter stated that they do not engage in mediatin activities and are therefore part of the MU-NO-group). In the group of MU-CAMs, however, the percentage of women outweighs men: 56.2% are female, 41.7% male. The picture is reversed for the group of MU-NOs: 58.3% of male and 43.8% of female respondents in this group refrain from integrating mediating activities into their work portfolio.↩︎

The concept of music mediation, like that of cultural and art mediation (cf. e.g. Mörsch n.d.), is difficult to grasp, as it refers to heterogeneous practices that are constantly transforming and expanding, and the theoretical approaches and perspectives can also vary greatly. About music mediation as a “messy concept”, see Chaker and Petri-Preis (2022, 12-17).↩︎

To determine the probability of error, statistical significance tests were carried out for the data sets of the special analysis, whereby the chi-square test was mostly used if nominal data was given. However, the expected cell frequencies very often have a value of less than 5, which means that the respective significance calculation may be erroneous and therefore invalid. For this reason, the p-value is not given in this article.↩︎

Looking at the median value, that is the central value, makes sense if one assumes that the results may be distributed very unevenly, for example that there are a few top earners (in the field of classical music, for example, top soloists or musicians in star orchestras such as the Vienna Philharmonic) who increase the arithmetic mean. The median divides the distribution into two subsets. Up to a maximum of 50% of the distribution lies below the median value.↩︎

For example, the highest median value in the field of the arts was found for the film sector at €17,500 net in 2017 (Wetzel et al. 2018, 198).↩︎

A brief interpretative note on this result: dropping out of university is not uncommon in the field of music and the reasons for this step are varied and individual (e.g. personal, psychological, social). However, musicians who want to make a living mostly from artistic work, in particular, often leave educational institutions such as universities and conservatories without a degree, for example if they have successfully completed an audition for an orchestra or are able to secure sufficiently attractive project commissions.↩︎

Altreiter, Carina. 2023. “Arbeitssoziologie als transformative Wissenschaft. Ein Debattenbeitrag.” Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft 49, no. 2: 125-147. DOI: 10.59288/wug492.177.

Banks, Mark, and David Hesmondhalgh. 2009. “Looking for Work in Creative Industries Policy.” International Journal of Cultural Policy, Issue 15, no. 4: 415-430. DOI: 10.1080/10286630902923323.

Benhamou, Françoise. 2003. “Artists’ Labour Markets.” In A Handbook of Cultural Economics, edited by Ruth Towse, 69-75. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. DOI: 10.4337/9781781008003.00013.

Bennett, Dawn. 2016. Understanding the Classical Music Profession. The Past, The Present and Strategies for the Future. New York: Routledge.

Blaukopf, Kurt. 1989. “Westernisation, Modernisation and the Mediamorphosis of Music.” International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 20, no. 2: 183-192.

Chaker, Sarah, and Axel Petri-Preis. 2019. “Professionalisation in the Field of Music Mediation (Musikvermittlung).” Lecture (unpublished) given at the conference isa science, 7-11 August 2019, Reichenau an der Rax: University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna.

Chaker, Sarah, Matthias Gruber, and Axel Petri-Preis. 2019. “Musikvermittlung – einige Anmerkungen zum Begriff und neue empirische Daten aus dem Berufsfeld.” Lecture (unpublished) given at the Forum an Hochschulen und Universitäten, 22. November 2019, Hochschule der Künste Bern.

Chaker, Sarah, and Axel Petri-Preis. 2020. “Professional Musicians as Educators. Activities, Challenges, Motivations.” Unpublished lecture given in course of the conference Creative Identities in Transition“, 27-29 February 2020, University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna.

———. 2022. “Musikvermittlung and Its Innovative Potential. Terminological, Historical and Sociological Remarks.” In Tuning Up! The Innovative Potential of Musikvermittlung, edited by Sarah Chaker, and Axel Petri-Preis, 11-38. Bielefeld: transcript.

———. 2023. Opening speech (unpublished) at the conference Turning Social. On the Social-Transformative Potential of Music Mediation, 15-16 June 2023, University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna.

Coulson, Susan. 2012. “Collaborating in a Competitive World: Musicians’ Working Lives and Understanding of Entrepreneurship.” Work, Employment and Society 26, no. 2: 246-261. DOI: 10.1177/0950017011432919.

Döring, Nicola, and Jürgen Bortz. 2016. “Stichprobenziehung.” In Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften (5th edition), 291-319, Wiesbaden: Springer.

Durkheim, Emile. 1984 [1895]. Die Regeln der soziologischen Methode. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

EDUCULT, and Netzwerk Junge Ohren e.V. (eds.). 2020. Arbeitsbedingungen für Musikvermittler*innen im deutschsprachigen Raum: Hochmotiviert, exzellent ausgebildet, prekär bezahlt: Auswertung der gleichnamigen Umfrage im April 2018. Berlin: Netzwerk Junge Ohren e.V.

Elliott, David, Marissa Silverman, and Wayne D. Bowman. 2016. Artistic Citizenship. Artistry, Social Responsibility, and Ethical Practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Engelmann, Maike, Lorenz Grünewald, and Julia Heinrich. 2012. “The New Artrepreneur: How Artists Can Thrive on a Networked Music Business.” International Journal of Music Business Research 1, no. 2 (October): 31-45.

Gee, Kate, and Pamela Yeow. 2021. “A Hard Day’s Night: Building Sustainable Careers for Musicians.” Cultural Trends 30, no. 4: 338-354. DOI: 10.1080/09548963.2021.1941776.

Gensch, Gerhard, and Herbert Bruhn. 2008. “Der Musiker im Spannungsfeld zwischen egabungsideal, berufsbild und Berufspraxis im digitalen Zeitalter.” In Musikrezeption, Musikdistribution, Musikproduktion. Der Wandel des Wertschöpfungsnetzwerks in der Musikwirtschaft, edited by Gerhard Gensch, Eva Maria Stöckler, and Peter Tschmuck, 3-23. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Giroux, Henry Armand. 2005. “The Terror of Neoliberalism: Rethinking the Significance

of Cultural Politics.” College Literature 32, no.1: 1-19. DOI: 10.1353/lit.2005.0006.

Gutzeit, Reinhart von. 2014. “Musikvermittlung – was ist das nun wirklich? Umrisse und Perspektiven eines immer noch jungen Arbeitsfeldes.” In Musikvermittlung – wozu? Umrisse und Perspektiven eines jungen Arbeitsfeldes, edited by Wolfgang Rüdiger, 19-36. Mainz: Schott.

Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

Harvie, Jen. 2013. Fair Play – Art, Performance and Neoliberalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Haynes, Jo, and Lee Marshall. 2017. “Reluctant Entrepreneurs: Musicians and Entrepreneurship in the ‘New’ Music Industry.” The British Journal of Sociology 69, no. 2 (June): 459-482. DOI: 10.1111/1468-4446.12286.

Hesmondhalgh, David. 1996. “Flexibility, post-Fordism and the music industries.” Media, Culture & Society 18, no. 3 (July): 469-488. DOI: 10.1177/016344396018003006.

Kubacki, Krzysztof, and Robin Croft. 2011. “Markets, Music and All That Jazz.” European Journal of Marketing, vol. 45 no. 5, 805-821. DOI: 10.1108/03090561111120046.

Menger Pierre-Michel. 1999. “Artistic Labor Markets and Careers.” Annual Review of Sociology 25, 541-574.

Mörsch, Carmen. n.d. Zeit für Vermittlung. Eine online Publikation zur Kulturvermittlung, edited by the Institute for Art Education at the Zürcher Hochschule der Künste (ZHdK), on behalf of Pro Helvetia. Accessed September 27, 2024. kultur-vermittlung.ch/zeit-fuer-vermittlung/download/pdf-d/ZfV_0_gesamte_Publikation.pdf.

Pankoke, Eckart. 2010. “Soziale Frage.” In Grundbegriffe der Soziologe, edited by Johannes Kopp, and Bernhard Schäfers, 260-265. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Paulus, Aljoscha. 2018. “The Dark Side of the Musicpreneur: Über Probleme einer neoliberalen Perspektivierung musikalischer Arbeit und die Frage nach kollektiven Widerstandspotenzialen.” [‘The Dark Side of the Musicpreneur: On the Problems of a Neoliberal Perspective of Musical Work and the Question of Potentials for Collective Resistance.’] Zeitschrift für Kulturmanagement 4, no. 2 (December): 129-158. DOI: 10.14361/zkmm-2018-0206.

Petri-Preis, Axel. 2022. Musikvermittlung lernen. Analysen und Empfehlungen zur Aus- und Weiterbildung von Musiker_innen. Bielefeld: transcript.

———. 2023. “Wer arbeitet musikvermittlend?” In Handbuch Musikvermittlung. Studium, Lehre, Berufspraxis, edited by Axel Petri-Preis, and Johannes Voit, 95-99. Bielefeld: transcript.

Petri-Preis, Axel, and Johannes Voit. “Was ist Musikvermittlung?” In Handbuch Musikvermittlung. Studium, Lehre, Berufspraxis, edited by Axel Petri-Preis, and Johannes Voit, 25-30. Bielefeld: transcript.

Prokop, Rainer, and Rosa Reitsamer. 2023. “The DIY Careers of Young Classical Musicians in Neoliberal Times.” DIY, Alternative Cultures & Society 1, no. 2 (August): 111-124. DOI: 10.1177/27538702231174197.

Rangadhithya RV, and Veluchamy Ramanujam. 2022. “A Study on Musicpreneurs Perception Towards their Music Career.” International Journal of Marketing and Human Resource Management (IJMHRM), 13, no. 2: 1-7.

Rattle, Sir Simon. 2004. “Rhythm is it!” Excerpt from the film, provided by Koen Mertens on YouTube. Accessed May 30, 2024. www.youtube.com/watch?v=W9mneDmFd0g.

Renza, Victor, Kirsti R. Andersen, Christian Fieseler, Fiona McDermott, and Róisin McGannon. 2024. “The Arts Mobilizing Communities: From Socially Engaged Arts to Social Artrepreneurship.” In Art and Sustainability Transitions in Business and Society, edited by Hanna Lehtimäki, Steven S. Taylor, and Mariana Galvão Lyra. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-44219-3_4.

Schelepa, Susanne, Petra Wetzel, Gerhard Wohlfahrt, and Anna Mostetschnig. 2008. Zur sozialen Lage der Künstler und Künstlerinnen in Österreich. Wien: L&R Sozialforschung, im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur.

Schippling, Joshua, and Johannes Voit. 2023. “Dialoggruppen der Musikvermittlung.” In Handbuch Musikvermittlung. Studium, Lehre, Berufspraxis, edited by Axel Petri-Preis, and Johannes Voit, 179-196. Bielefeld: transcript.

Smilde, Rineke. 2022. “Engaging with New Audiences – Perspectives of Professional Musicians’ Biographical Learning and Its Innovative Potential for Higher Music Education.” In Tuning Up! The Innovative Potential of Musikvermittlung, edited by Sarah Chaker, and Axel Petri-Preis, 151-168. Bielefeld: transcript.

Smudits, Alfred. 2002. Mediamorphosen des Kulturschaffens. Kunst und Kommunikationstechnologien im Wandel. Wien: Braumüller.

———. 2008. “Soziologie der Musikproduktion.” In Musikrezeption, Musikdistribution, Musikproduktion. Der Wandel des Wertschöpfungsnetzwerks in der Musikwirtschaft, edited by Gerhard Gensch, Eva Maria Stöckler, and Peter Tschmuck, 241-265. Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Schwetter, Holger. 2018. “From Record Contract to Artrepreneur? Musicians’ Self-Management and the Changing Illusio in the Music Market.” Kritika Kultura 32: 183-207.

Voit, Johannes, and Constanze Wimmer. 2023. “Vorwort.” In Handbuch Musikvermittlung. Studium, Lehre, Berufspraxis, edited by Axel Petri-Preis, and Johannes Voit, 13. Bielefeld: transcript.

Wetzel, Petra, Lisa Danzer, Veronika Ratzenböck, Anja Lungstraß, and Günther Landsteiner. 2018. Soziale Lage der Kunstschaffenden und Kunst- und Kulturvermittler/innen in Österreich. Ein Update der Studie ‚Zur sozialen Lage der Künstler und Künstlerinnen in Österreich‘ 2008. Wien: L&R Sozialforschung / österreichische kulturdokumentation im Auftrag des Bundeskanzleramtes – Sektion Kunst und Kultur.

Wetzel, Petra. 2019a. Tabellenband Sonderauswertung: Musiker/innen, die auch kunst- und kulturvermittelnd aktiv sind. Wien: L&R Sozialforschung, im Auftrag des Instituts für Musiksoziologie an der mdw – Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien. In possession of the author.

———. 2019b. Mail correspondence with Sarah Chaker. In possession of the author.

Whitney, Ian, Jennifer Rowley, and Dawn Bennett. 2021. “Developing Student Agency: ePortfolio Reflections of Future Career Among Aspiring Musicians.” International Journal of ePortfolio 11, no. 1: 53-65.

Wimmer, Constanze. 2010. Musikvermittlung im Kontext. Impulse – Strategien – Berufsfelder. Regensburg: ConBrio.

———. 2021.“Musikvermittler.” In Lexikon der Musikberufe, edited by Martin Lücke, 458-464. Lilienthal.